Opioid analgesics work by binding to one or more of the opioid receptors. Opioid analgesics are primarily of three types: Opioid agonists: Full opioid agonists relieve pain by stimulating opioid receptors on neurons, which inhibit the release of chemicals (neurotransmitters) that transmit pain signals.

How to overcome opioids?

The opioid epidemic remains a U.S. public health crisis and has only worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, with opioid deaths accounting for 69,000 of 93,000 overdose-related deaths in 2020, according to provisional drug overdose data ...

What are opioids and why are they dangerous?

When opioid medications travel through your blood and attach to opioid receptors in your brain cells, the cells release signals that muffle your perception of pain and boost your feelings of pleasure. What makes opioid medications effective for treating pain can also make them dangerous.

How do topical analgesics really work?

Topical analgesics are medications that are applied on the skin to relieve muscle, joint or nerve pain.Topical analgesics get absorbed by the skin and act on the tissue beneath. There are many types of topical analgesics and each works in a unique way to relieve pain.. Many of the topical analgesics relieve pain by reducing inflammation and locally numbing the area.

What is the purpose of opioid analgesics?

- Tolerance—meaning you might need to take more of the medication for the same pain relief

- Physical dependence—meaning you have symptoms of withdrawal when the medication is stopped

- Increased sensitivity to pain

- Constipation

- Nausea, vomiting, and dry mouth

- Sleepiness and dizziness

- Confusion

- Depression

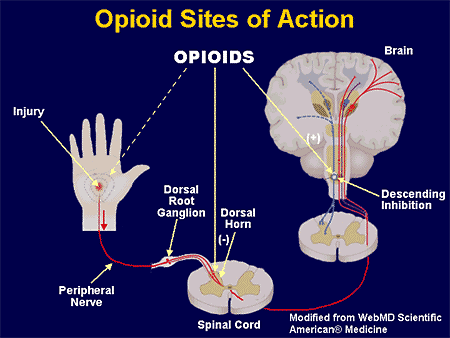

What is the action of opioid analgesics?

Presynaptically, opioid analgesics act on primary nociceptive afferents (inhibition of calcium channels), resulting in the reduced release of neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate implicated in nociceptive transmission.

How do opioids affect the pain pathway?

They block pain at the site of the noxious signal. Opioids block the neurotransmitter dopamine. Opioids bind to receptors in the peripheral and CNS to block pain signals. Opioids increase serotonin throughout the brain.

How do opioids work chemically?

Opioids work by activating opioid receptors on nerve cells. These receptors belong to a family of proteins known as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Scientists have always assumed that all opioids—whether produced by the body (endogenously) or taken as a drug—interact in the same way with opioid receptors.

Do opioids inhibit pain?

B, Opioids produce their analgesic effects by inhibiting spinal nociceptive transmission. On presynaptic nerve terminals, opioids reduce cAMP signaling and suppress activity of voltage-gated calcium channels, which inhibits release of nociceptive transmitters.

How are opioid analgesics used?

Opioid analgesics come in many formulations and strengths. Opioid analgesics are administered through several routes such as:

What is an opioid analgesic?

Opioid analgesics are medications prescribed for the management of acute and chronic pain in many conditions. Opioid analgesics are also used to treat opioid use disorder. Opioid medications have a high risk for addiction and must be used with great caution.

Why are partial opioid agonists effective?

Partial opioid agonists: Partial opioid agonists elicit a partial functional response because they work as agonists in some receptors and antagonists in others , and consequently, produce fewer adverse effects than full agonists while being effective for pain relief ( analgesia ).

How many different opioid receptors are there in the human body?

The five different opioid receptors discovered in the human body are:

Why are opioids used for diarrhea?

Some opioid analgesics are used to treat diarrhea because they inhibit stomach acid secretion and gastrointestinal propulsion and motility. Opioid analgesics should be used with caution in patients with kidney or liver impairment.

Do opioids bind to receptors?

All opioid analgesics bind to opioid receptor s but work in different ways. Opioid receptors are protein molecules on nerve cell ( neuron) membranes in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Opioid receptors mediate the body’s response to most hormones and some of their functions include modulating pain, stress response, respiration, digestion, mood, and emotion.

Can naloxone be used to reverse opioid effects?

Opioid overdose can have severe consequences, and naloxone, an opioid antagonist, is administered to reverse opioid effects in case of opioid overdose. Opioid analgesics are typically never abruptly discontinued, but tapered with an opioid agonist /antagonist combination before weaning off.

What is opioid analgesia?

Opioid analgesia is indicated for the management of pain in patients where an opioid analgesic is appropriate. What, exactly, the term appropriate constitutes has been a recently contentious issue. Center for Disease Control and Prevention's 2016 guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain state that "clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function will outweigh risks to the patient. When using opioids, it should be in combination with nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy, as appropriate." In the same guidelines, the CDC defines the indication of opioid use for acute pain, stating that "when opioids are used for acute pain, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and should prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed." [1][2][3][4][2]

How do opioids work?

Presynaptically, opioids block calcium channels on nociceptive afferent nerves to inhibit the release of neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate, which contribute to nociception. Postsynaptically, opioids open potassium channels, which hyperpolarize cell membranes, increasing the required action potential to generate nociceptive transmission. The mu, kappa, and delta-opioid receptors mediate analgesia spinally and supraspinally. [5]

What is an opioid?

Opioids are a class of medication used in the management and treatment of pain. This activity outlines the indications, action, and contraindications for opioids as a valuable agent in the treatment of acute and chronic pain. This activity will highlight the mechanism of action, adverse event profile, and other key factors (e.g., off-label uses, dosing, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, monitoring, relevant interactions) pertinent for members of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with various forms of pain and related conditions.

Which opioids cause serotonin?

As mentioned above, opioids with serotonergic activity such as tramadol, oxycodone, fentanyl, methadone, dextromethorphan, meperidine, codeine, and buprenorphine have the potential to cause serotonin syndrome when used with other agents with serotonergic activity.[8] Therefore, coadministration with other serotonergic active medications should be done cautiously or avoided entirely.

Can opioids affect serotonin?

Also, some opioid agents can affect serotonin kinetics in the presence of other serotonergic agents. The proposed mechanism for this is through either weak serotonin reuptake inhibition and increased the release of intrasynaptic serotonin through inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acidergic presynaptic inhibitory neuron on serotonin neurons. These opioids include tramadol, oxycodone, fentanyl, methadone, dextromethorphan, meperidine, codeine, and buprenorphine. These opioids have the potential to cause serotonin syndrome and should be used cautiously with other agents with serotonergic activity.

Do opioids need to be monitored?

The degree of monitoring for patients prescribed opioid analgesics is highly provider-dependent. All providers should see patients for routine follow-up visits that include a history and physical exam to monitor for adverse effects listed previously. Many providers employ a wide variety of other tactics to monitor for signs of abuse, including assessment surveys, state prescription drug monitoring programs, frequent visits with urine toxicology screens, use of adherence check-lists, motivational counseling, and pill counts. [9]

Does methadone bind to glutamate?

Opioids such as methadone also have activity at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Methadone binds to the NMDA receptor and antagonizes the effect of glutamate, which theoretically explains why methadone has efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic pain above other opioids. [6]

How do opioids produce their effects?

Morphine and synthetic opioid analgesics produce their effects largely by acting as agonists at specific opioid receptors in the CNS. Opioid drugs show receptor selectivity and can have agonist, partial agonist or antagonist properties at various opioid receptor types ( Table 19.1 ). The analgesic action of opioids is the result of a complex series of neuronal interactions. In the nucleus raphe magnus of the brain, µ-receptor stimulation decreases activity in inhibitory GABA neurons that project to descending inhibitory serotonergic neurons in the brainstem. These neurons in turn connect presynaptically with afferent nociceptive fibres in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Inhibition of the GABA neurons permits increased firing of the descending inhibitory serotonergic neurons. Analgesia is produced by inhibition of the release of the pain pathway mediators, substance P, glutamate and nitric oxide from the afferent nociceptive neurons ( Fig. 19.5 ). Activation of κ-receptors antagonises the analgesia produced by µ-receptor stimulation, by inhibiting the descending (pain-modulating) serotonergic neurons in the pain pathway. However, there is a paradoxical spinal analgesic effect from unopposed κ-receptor activation.

What stimuli stimulate the release of substances that act to promote pain?

Tissue injury and other noxious stimuli such as heat or extremes of pH can stimulate the release of substances that act to promote pain, such as bradykinin (BK) and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT). Prostaglandin E 2 (PGE 2) acting at prostaglandin E receptors (EP) sensitises the nerve endings to the actions of nociceptive mediators ...

How do prostaglandins affect the nociceptive nerve?

Prostaglandins enhance nociceptive impulses in peripheral afferent neurons by enhancing the ability of thermal, mechanical or chemical stimuli to increase Na + /Ca 2+ influx and thereby to generate action potentials in nociceptive afferent neurons. NSAIDs inhibit the production of prostaglandins by the cyclo-oxygenase type 1 and type 2 (COX-1, COX-2) isoenzymes and thereby reduce the sensitivity of sensory nociceptive nerve endings to agents released by injured tissue that initiate pain, such as bradykinin and substance P. NSAIDs may also act on pain pathways in the CNS. Paracetamol, although not usually considered to be an NSAID, may also work in part through the same pathways. These drugs are considered fully in Chapter 29.

What is the effect of nociceptive pathways on pain?

Prolonged activation of the nociceptive pathways can produce pathophysiological and phenotypic changes resulting in neuropathic pain that persists when the original pathological cause of the pain has resolved, and generation of nociceptive signals can occur at low levels of axonal stimulation.

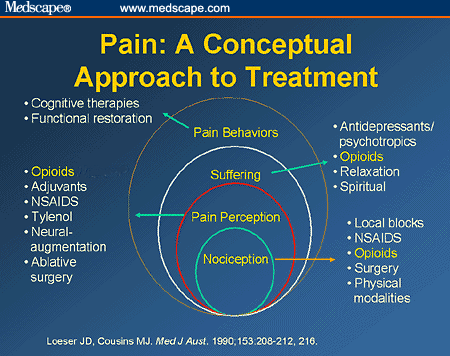

What is nociceptive pain?

Nociceptive pain is a defensive response to a variety of stimuli (e.g. mechanical, thermal or chemical) that activate nociceptor sensory units on nerve endings. It is defensive as it induces behaviour that avoids exacerbation of the pain, and allows us to protect a damaged part of the body while it heals. Painful stimuli are transmitted ...

What is neuropathic pain?

Neuropathic pain may result from abnormal neuronal activity that persists beyond the time expected for healing of the injury. Examples include phantom limb pain following amputation and shingles causing pain well beyond the healing of the injury. There are multiple pathophysiological mechanisms underlying neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain can be spontaneous (stimulus-independent), when it is usually described by the sufferer as shooting or lancinating sensations, electric shock-like pain or an abnormal unpleasant sensation (dysaesthesia). Alternatively, it can be an exaggerated response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a trivial stimulus (allodynia).

Which receptors are present on the peripheral nerves in the pain pathways?

Opioid analgesics. Opioid receptors are also present on peripheral nerves in the pain pathways, and a µ-receptor agonist reduces the sensitivity of peripheral nociceptive neurons to pain stimuli, particularly in inflamed tissues.

What is the most effective pain medication?

Opioids have been regarded for millennia as among the most effective drugs for the treatment of pain. Their use in the management of acute severe pain and chronic pain related to advanced medical illness is considered the standard of care in most of the world. In contrast, the long-term administration of an opioid for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain continues to be controversial. Concerns related to effectiveness, safety, and abuse liability have evolved over decades, sometimes driving a more restrictive perspective and sometimes leading to a greater willingness to endorse this treatment. The past several decades in the United States have been characterized by attitudes that have shifted repeatedly in response to clinical and epidemiological observations, and events in the legal and regulatory communities. The interface between the legitimate medical use of opioids to provide analgesia and the phenomena associated with abuse and addiction continues to challenge the clinical community, leading to uncertainty about the appropriate role of these drugs in the treatment of pain. This narrative review briefly describes the neurobiology of opioids and then focuses on the complex issues at this interface between analgesia and abuse, including terminology, clinical challenges, and the potential for new agents, such as buprenorphine, to influence practice.

What is tolerance to opioids?

According to the consensus document, tolerance is defined as a decreased subjective and objective effect of the same amount of opioids used over time, which concomitantly requires an increasing amount of the drug to achieve the same effect. Although tolerance to most of the side effects of opioids (e.g., respiratory depression, sedation, nausea) does appear to occur routinely, there is less evidence for clinically significant tolerance to opioids– analgesic effects ( Collett, 1998; Portenoy et al., 2004 ). For example, there are numerous studies that have demonstrated stable opioid dosing for the treatment of chronic pain (e.g., Breitbart, et al., 1998; Portenoy et al., 2007) and methadone maintenance for the treatment of opioid dependence (addiction) for extended periods ( Strain and Stitzer, 2006 ). However, despite the observation that tolerance to the analgesic effects of opioid drugs may be an uncommon primary cause of declining analgesic effects in the clinical setting, there are reports (based on experimental studies) that some patients will experience worsening of their pain in the face of dose escalation ( Ballantyne, 2006 ). It has been speculated that some of these patients are not experiencing more pain because of changes related to nociception (e.g. progression of a tissue-injuring process), but rather, may be manifesting an increase in pain as a result of the opioid-induced neurophysiological changes associated with central sensitization of neurons that have been demonstrated in preclinical models and designated opioid-induced hyperalgesia ( Mao, 2002; Angst & Clark, 2006 ). Analgesic tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia are related phenomena, and just as the clinical impact of tolerance remains uncertain in most situations, the extent to which opioid-induced hyperalgesia is the cause of refractory or progressive pain remains to be more fully investigated. Physical dependence represents a characteristic set of signs and symptoms (opioid withdrawal) that occur with the abrupt cessation of an opioid (or rapid dose reduction and/or administration of an opioid antagonist). Physical dependence symptoms typically abate when an opioid is tapered under medical supervision. Unlike tolerance and physical dependence which appear to be predictable time-limited drug effects, addiction is a chronic disease that “represents an idiosyncratic adverse reaction in biologically and psychosocially vulnerable individuals” ( ASAM, 2001 ).

How many people have chronic pain?

The prevalence of chronic pain in the general population is believed to be quite high, although published reports have varied greatly. Cautious cross-national estimates of chronic pain range from 10% ( Verhaak et al., 1998) to close to 20% ( Gureje, Simon, & Von Korff, 2001 ), which would represent 30 to 60 million Americans. A national survey of 35,000 households in the US, conducted in 1998, estimated that the prevalence among adults of moderate to severe non-cancer chronic pain was 9% ( American Pain Society, 1999 ). A large survey (N=18,980) of general populations across several European countries reported that the prevalence for chronic painful physical conditions was 17.1% ( Ohayon & Schatzberg, 2003 ).

How prevalent is substance abuse in chronic pain?

One 1992 literature review found only seven studies that utilized acceptable diagnostic criteria and reported that estimates of substance use disorders among chronic pain patients ranged from 3.2% – 18.9% ( Fishbain, Rosomoff, & Rosomoff, 1992 ). A Swedish study of 414 chronic pain patients reported that 32.8% were diagnosed with a substance use disorder ( Hoffmann, Olofsson, Salen, & Wickstrom, 1995 ). In two US studies, 43 to 45% of chronic pain patients reported aberrant drug-related behavior; the proportion with diagnosable substance use disorder is unknown ( Katz et al., 2003 ; Passik et al., 2004 ). All these studies evaluated patients referred to pain clinics and may overstate the prevalence of substance abuse in the overall population with chronic pain.

Can opioids help with CNMP?

This consensus, however, has received little support in the literature. Systematic reviews on the use of opioids for diverse CNMP disorders report only modest evidence for the efficacy of this treatment ( Trescot et al., 2006; 2008 ). For example, a review of 15 double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trials reported a mean decrease in pain intensity of approximately 30% and a drop-out rate of 56% only three of eight studies that assessed functional disturbance found improvement ( Kalso, Edwards, Moore, & McQuay, 2004 ). A meta-analysis of 41 randomized trials involving 6,019 patients found reductions in pain severity and improvement in functional outcomes when opioids were compared with placebo ( Furlan, Sandoval, Mailis-Gagnon, & Tunks, 2006 ). Among the 8 studies that compared opioids with non-opioid pain medication, the six studies that included so-called “weak” opioids (e.g., codeine, tramadol) did not demonstrate efficacy, while the two that included the so-called “strong” opioids (morphine, oxycodone) were associated with significant decreases in pain severity. The standardized mean difference (SMD) between opioid and comparison groups, although statistically significant, tended to be stronger when opioids were compared with placebo (SMD = 0.60) than when strong opioids where compared with non-opioid pain medications (SMD = 0.31). Other reviews have also found favorable evidence that opioid treatment for CNMP leads to reductions in pain severity, although evidence for increase in function is absent or less robust ( Chou, Clark, & Helfand, 2003; Eisenberg, McNicol, & Carr, 2005 ). Little or no support for the efficacy of opioid treatment was reported in two systematic reviews of chronic back pain ( Deshpande, Furlan, Mailis-Gagnon, Atlas, & Turk, 2007; Martell, et al., 2007 ). Because patients with a history of substance abuse typically are excluded from these studies, they provide no guidance whatsoever about the effectiveness of opioids in these populations.

Can withdrawal from opioids cause pain?

For example, based on anecdotal evidence from chronic pain patients, withdrawal from opioids can greatly increase pain in the original pain site. These phenomena suggest the need to carefully assess the potential for withdrawal during long-term opioid therapy (e.g, at the end of a dosing interval or during periods of medically-indicated dose reduction).

What are the influences of chronic pain?

Chronic pain also is influenced by psychosocial and psychiatric disturbances, such as cultural influences, social support, comorbid mood disorder, and drug abuse ( Gatchel, Peng, Peters, Fuchs & Turk, 2007 ). Classic studies of pain behavior indicate that cultural differences in the beliefs and attitudes towards pain (e.g., Zbrowski, 1969) and the social/environmental context of the pain (e.g., Beecher, 1959 ) have a significant impact on pain behaviors.

How to optimize opioid use?

To optimize use of opioids, avoid those that have not been studied in older adults, start with the lowest available dose of an immediate-release product, and consult pharmacists or pain experts for challenging cases, including those requiring high doses.

How do opioids change with age?

Unlike absorption and distribution, however, age-related changes in metabolism are more apparent. All opioids are metabolized by the liver; Table 2lists those opioids that undergo phase I and phase II metabolism via respective isoenzymes. In general, drugs metabolized in phase I via the cytochrome P450 enzyme system will undergo oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis. Age-related reduction in CYP3A4 function may affect opioids, resulting in decreased systemic clearance and subsequent increased elimination half-life. Specifically, the systemic clearance of oxycodone and, possibly, buprenorphine have been shown to decline with age.16,20,21The effect of age on fentanyl clearance in older adults, however, is unclear.22Although not explicitly studied in the elderly, both levorphanol and methadone have half-lives exceeding 12 hours; as such, the prescription of these opioids should be restricted to those practitioners with considerable experience.23

How much oxycodone is equivalent to tramadol?

Cross-tolerance must be taken into consideration if switching opioids. The conversion factor 50 mg tramadol = 10 mg oxycodone = 10 mg oral morphine equivalents (OME) may be used to convert between opioids. Lower the daily dose of the newly-prescribed opioid by 25–50% OME. For example, when converting from tramadol 200 mg daily to oral morphine, 200 mg = 40 OME. The appropriate dose of morphine is 10 mg every 12 hours, and then 5 mg every 6 hours as needed for breakthrough pain.

What are the three opioids that we recommend prioritizing?

We recommend prioritizing those opioids (tramadol, oxycodone, and morphine) in which pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy studies have been conducted in the elderly.

What are the effects of age related changes in pharmacokinetics?

Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics (e.g., declines in hepatic and renal function) and pharmacodynamics make older adults more susceptible to adverse consequences associated with opioids, including falls, fractures, and delirium.

Can opioids be used for non-cancer pain?

When possible, chronic non cancer pain (CNCP) in older adults should be managed by nonpharmacological modalities in conjunction with non-opioid analgesics. If moderate to severe pain persists despite these approaches, however, non-parenteral opioids (Table 1) may be considered as adjunctive therapy.1,2This article will discuss the epidemiology of opioid use and their effectiveness for CNCP in older adults, as well as review age-related changes in opioid pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics that increase the risks of adverse effects in the elderly. Finally, to assist clinicians with selecting appropriate therapy, the article concludes with an evidence-based approach to optimize opioid prescribing in older adults.

Does tramadol have a renal function?

Furthermore, renal function, which can be estimated by glomerular filtration rate (GFR), is reduced with age.18Codeine, hydromorphone, meperidine, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol all have renally-cleared, active metabolites (Table 2). Consequently, age-related declines in renal function may lead to opioid toxicity with these opioids due to the accumulation of these active metabolic byproducts. Specifically, meperidine should be avoided in older adults because accumulation of its active metabolite (normeperidine) can cause neurotoxicity. 29Only tramadol has specific dosing guidelines in those with reduced GFR.29

What is an opioid analgesic?

Opioid analgesics encompass a wide range of medicinal products that typically share the ability to relieve acute severe pain through their action on the µ opioid receptor— the major analgesic opioid receptor expressed throughout the nervous system. Since the isolation of morphine from crude opium by Sertürner in 1803, there has been a progressive increase in the number of opioid analgesics that differ in their chemical composition, route of administration, uptake, distribution, type/rate of elimination, and ability to bind to opioid receptors. Certain of these drugs have ultra-short durations of action uniquely suited to providing analgesia as a component of a balanced surgical anesthetic. Others have very long durations of action resulting either from the intrinsic properties of the opioid molecule or the pharmaceutical formulation; in either case, these opioids are released at a predictable rate into a patient's body. An additional feature of these medications contributing to their clinical utility is the availability of oral, intravenous, transdermal, intranasal, epidural, and intrathecal preparations.

What is the acute pain context of opioids?

Another commonly encountered acute pain context leading to opioid exposure is the treatment of acute injuries, such as those due to household, sporting, or motor vehicle accidents. In these situations, limited supplies of opioids may be prescribed by emergency departments, urgent care clinics, specialty physicians, and primary care providers. The prescribing of opioids by emergency departments has been especially closely studied, and an increase was found to coincide with an increase in overall opioid prescribing (Maughan et al., 2015). Prescribing in this context can set the stage for a pattern of more chronic use; indeed, observational evidence suggests that long-term opioid use may begin in the emergency department (with 1 in 48 patients prescribed opioids becoming long-term users) (Barnett et al., 2017). Likewise, the use of prescription opioids by former professional athletes is very high, and participants in interscholastic sports may have an elevated risk of opioid use and misuse relative to their nonathlete counterparts (Veliz et al., 2015). Motor vehicle accidents, particularly severe ones, also appear to lead to chronic opioid use in some patients (Zwisler et al., 2015). Opioid prescribing guidelines targeting emergency departments and other acute care settings might contribute to reducing opioid prescribing and increase the use of such measures as urine drug screening prior to prescribing (Chen et al., 2016; del Portal et al., 2016).

What is the ICD-9 code for opioids?

Tracking of opioid prescriptions currently is not linked to such details as medical indication, whether the patient's pain is acute or chronic, or other pertinent details of medical history. Rather, the primary tracking factors are the 9th and 10th revisions of the International Classification of Diseases(ICD) (Pan, 2016). On this basis, diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissues (ICD-9 codes 710–739) are among the conditions most commonly associated with the use of opioids (FDA, 2016; Pan, 2016). According to office-based physician reports, in 2015 nearly 54 percent of diagnoses of chronic conditions associated with use of hydrocodone/acetaminophen were for diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissues (which include arthritis and back pain). Among acute conditions, injuries (fractures, sprains, and contusions [ICD-9 codes 800–999]) were the conditions most commonly associated with the use of hydrocodone/acetaminophen (42 percent), followed by diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissues (17 percent) (FDA, 2016). Cumulative ICD data for the period January 2007–November 2011 indicate that the shares of musculoskeletal system and connective tissue diagnoses associated with the use of different types of opioids were as follows: morphine ER (68 percent), morphine IR (56 percent), oxycodone IR (41 percent), hydrocodone combination (25 percent), and oxycodone combination (20 percent) (Pan, 2016). The shares of individuals with fractures, sprains, and contusions using various types of opioids were considerably different, with oxycodone combination (26 percent) and hydrocodone combination (19 percent) dominating, followed by oxycodone IR (8 percent), morphine ER (3 percent), and morphine IR (4 percent) (Pan, 2016). Based on these data, it appears that oxycodone IR and morphine IR and ER, as opposed to combination products, have been used more frequently to treat chronic pain associated with musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders.

What are the long term effects of opioids?

Of the many long-term consequences of using opioids, tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) are commonly cited as reasons for their waning therapeutic effect over time. Strong laboratory evidence demonstrates that these phenomena occur after even short periods of exposure to opioids or after exposure to large doses of the drugs (Angst and Clark, 2006; Trang et al., 2015; Yi and Pryzbylkowski, 2015). Likewise, tolerance and OIH have been demonstrated in people with OUD, and abnormal pain sensitivity in this population is associated with drug craving (Ren et al., 2009). On the other hand, OIH has been observed after short-term exposure to potent, rapidly eliminated opioids such as remifentanil in human volunteers (Angst and Clark, 2006; Eisenach et al., 2015). Correspondingly, patients for whom remifentanil is incorporated into their surgical anesthetic appear to have higher postoperative pain levels or opioid requirements consistent with either tolerance or OIH (de Hoogd et al., 2016; Fletcher and Martinez, 2014). However, the rapidity, severity, and pervasiveness of tolerance and OIH are poorly defined in chronic pain populations, as are possible differences among opioids with respect to causing these adverse consequences. The situation is made more problematic by difficulties in assessing tolerance and OIH in clinical settings. Rapid dose escalation with worsening pain and the spread of painful symptoms have been suggested as indicators of tolerance and OIH, but well-validated clinical methods for quantifying tolerance and OIH in chronic pain patients are lacking (Mao, 2002).

What is pain management and the opioid epidemic?

Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use.

What are the complications of opioids?

Among the complications now associated with the chronic use of opioids for pain are dependence, tolerance, hyperalgesia, addiction, hypogonadism, falls, fractures, sleep-disordered breathing, increased pain after surgery , and poorer surgical outcomes (Baldini et al., 2012; Chou et al., 2015).

How effective are opioids?

Opioids have long been used successfully to treat acute postsurgical and postprocedural pain, and they have been found to be more effective than placebo for nociceptive and neuropathic pain of less than 16 weeks' duration (Furlan et al., 2011). For other types of acute pain, however, such as low back pain, the efficacy of opioids is less clear (Deyo et al., 2015; Friedman et al., 2015). And as noted earlier, while evidence exists to support the use of opioids for the treatment of some acute and subacute pain, evidence to support their use to treat chronic pain is very limited (Chou et al., 2015; Dowell et al., 2016). The few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating the efficacy of opioids have had small sample sizes and rarely have produced data that extend past 3 months, the length of time after which pain is considered to be chronic.

How does analgesia work?

It produces analgesia by altering the pain perception in the brain but has a little anti-inflammatory effect. Opioid analgesics act on the mu-opioid receptors on the nerves in the periphery, spinal cord, and brain and reduce their excitability, in addition to preventing the transmission of pain signals.

What Are Analgesics?

Analgesics, or pain killers, are a group of agents that relieve pain due to inflammation. There are two main types of oral analgesics:

What is the first recommendation for pain management?

According to the WHO pain relief ladder, acetaminophen and NSAIDs are the first recommendations for the initial management of pain. If acetaminophen and NSAIDs are found ineffective, opioids can then be prescribed. (3)

What is tramadol used for?

It is most often used to treat postoperative or neuropathic pain. Because of its inferior efficacy and no clear benefit regarding safety compared with other alternatives, tramadol should not be a first-line oral analgesic. (12)

What is the best treatment for osteoarthritis?

3. Traditional NSAIDs/non-selective COX inhibitors. Traditional NSAIDs are more effective at reducing pain associated with concomitant inflammation, such as osteoarthritic pain and dysmenorrhea. An increase in the dose produces greater anti-inflammatory effects but also increases the adverse effects.

What is the effect of selective COX-2 inhibitors?

Selective COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs) inhibit the COX-2 enzyme primarily and thus exerts anti-inflammatory effects . Advertisements. Acetaminophen, or paracetamol, acts by a different mechanism by inhibiting the COX-3 enzyme in the brain.

How many people are affected by chronic pain?

A study on the global burden of chronic pain noted at least 10% of the world’s population is affected by a chronic pain condition, and every year, an additional 1 in 10 people develop chronic pain. (1) (2)