Health professionals are increasingly encouraged to involve patients in treatment decisions, recognising patients as experts with a unique knowledge of their own health and their preferences for treatments, health states, and outcomes. 1 2 Increased patient involvement, a result of various sociopolitical changes, w1 is an important part of quality improvement since it has been associated with improved health outcomes 3 w1-w9 and enables doctors to be more accountable to the public.

Full Answer

Should doctors involve patients in making treatment decisions?

Doctors are encouraged to involve patients in making treatment decisions, but this poses challenges for doctors Practical concerns include the extra time needed and the difficulties in eliciting patients' preferences, exacerbated by limited appropriate information to support patient involvement

How important is patient involvement in medical decision-making?

... Finally, in individual (micro) decision-making, the ethical and legal mandate for patient involvement in medical care is well-accepted as is the importance of patients expressing their preferences, and in engaging in informed choice in treatment decision-making (O'Connor et al., 1997;Say and Thomson, 2003).

Why is it important to engage patients in self-care decisions?

There is much evidence that engaging patients in treatment decisions and supporting their efforts at self-care can lead to beneficial outcomes. , Patients who are active participants in a shared decision-making process have a better knowledge of treatment options and more realistic perceptions of likely treatment effects.

Who is in control of your health care decisions?

Clearly there is no one model for all patients — patients have different desires in this regard, and varying healthcare literacy. Keep in mind, an adult competent patient is 100% in control of their own health care decision-making. The ultimate decision is always theirs.

Why are patient choices important?

Giving patients choices has been linked to their satisfaction. It has also been suggested that patient preferences are essential to good clinical care because the patient's cooperation and satisfaction reflect the degree to which medical intervention fulfils his or her choices, values, and needs.

Why is it important for patients to make informed decisions?

There are many benefits of making informed decisions, such as increased knowledge, sense of self-confidence, satisfaction with your care, and decreased anxiety and feelings of conflict about your decision.

Why is decision-making important in healthcare?

Participation in decision-making helps health care providers to understand patients' preferences in the treatment options. Also, it helps health care providers to determine the type of drugs that are suitable for the patient.

Why is decision making important for nurses?

The decisions nurses make while performing nursing care will influence their effectiveness in clinical practice and make an impact on patients' lives and experiences with health care regardless of which setting or country the nurse is practicing in.

What are some benefits of making good health decisions?

The decisions you make will influence your overall well-being as well as the quality and cost of your care. People who learn as much as they can about their choices often are more confident about the decisions they make.

Which benefit results from making informed healthcare decisions?

Which benefit results from making informed healthcare decisions? Every potential health issue is prevented. Individuals are empowered to take responsibility.

What must healthcare professionals do to help patients make decisions about their treatment?

Healthcare professionals must inform patients about advance directives and what types of treatments they may choose to accept or not accept. Copies of the advance directive (or its key points) must be in the patient's charts.

Why is patient participation important in health care?

Patients’ participation in decision making in health care and treatment is not a new area, but currently it has become a political necessity in many countries and health care systems around the world (3). A review of the literature reveals that participation of patients in health care has been associated with improved treatment outcomes. Moreover, this participation causes improved control of diabetes, better physical functioning in rheumatic diseases, enhanced patients' compliance with secondary preventive actions and improvement in health of patients with myocardial infarction (5-8). Emphasizing the importance of participation in decision making process motivates the service provider and the health care team to promote participation of patients in treatment decision making. These efforts include enhancement of patient access to multifaceted information providing systems and tools that help patients in decision making (9, 10). With enhanced patient participation, and considering patients as equal partners in healthcare decision making patients are encouraged to actively participate in their own treatment process and follow their treatment plan and thus a better health maintenance service would be provided (11).

What are the factors that influence patient participation?

In most studies, factors influencing patient participation consisted of: factors associated with health care professionals such as doctor-patient relationship, recognition of patient’s knowledge, allocation of sufficient time for participation, and also factors related to patients such as having knowledge, physical and cognitive ability, and emotional connections, beliefs, values and their experiences in relation to health services.

What databases are used to find patient participation?

General databases like Google Scholar, and specialized databases such as Medlib, Magiran, Iranmedex, SID, Scopus, Pubmed, Springer, and Science Direct , as well as textbooks addressing patients’ participation in healthcare were used. Keywords used to retrieve the relevant information from 1992 to 2012 were "patient engagement", "user involvement", "patient involvement", "patient participation", "decision making", "health care", "quantitative study", "qualitative study", "measurement", and "instrument".

Why are health care reforms important?

Of the most important reasons for the reforms in health care systems in developed countries in the last ten years are changes in people’s values, beliefs, and attitudes in respect of changes in community expectations, changes in patterns of diseases, increased life expectancy, and increasing emphasis on maximum level of health and quality of life, particularly in the last few years of life , which has been derived from the opinions of the public and the community . One of the most fundamental principles and policies of the new health care systems in these countries is valuing patients’ rights, and considering them as the axis for providing services, with special emphasis on the concept of patient and public participation and creating opportunities for all to share the decision on the method of receiving health care services.

What is patient participation?

Patient participation means involvement of the patient in decision making or expressing opinions about different treatment methods, which includes sharing information, feelings and signs and accepting health team instructions .

What are the skills of a healthcare practitioner?

The practitioner’s interpersonal communication skills (21) health care professional’s cultural competence, knowledge (knowing how to practice in a culturally informed and competent manner), beliefs and values (cultural, moral and professional), attitudes (respectful versus racist and ethnocentric toward ethnic minority patients), behavior (cultural skills and ability to form therapeutically effective relationships, engaging in cross-cultural communication, interviewing and assessing ethnic minority patients, addressing conflict, negotiating care, managing cases in a culturally informed and appropriate way) (17) health care professionals' knowledge and beliefs (18) features relating to the ethos and feel of healthcare encounters (welcoming; respectfulness; facilitation of patients’ contributions; and being non-judgmental) (22) patients’ relationship with professionals (3, 9), doctor listens and gives information (19), practitioners attending to patients’ views and patients feeling listened to; practitioners giving clear explanations based on their professional knowledge where patients understand these (22), considering the patient as an individual (23, 24), recognizing patients' knowledge (24), presence of a primary nurse/physician, encouragement of nurses and physicians to participate (19, 25), treating patients as equal partners in healthcare, nurses and physicians having enough time for patients(25).

Why are treatment options different?

This is because some cancers have subtypes and features that might have different treatment recommendations. For example, there are many types and subtypes of breast cancer and different ways to describe them. Some have special features that affect their treatment and outlook. There are also patient factors that tell the cancer care team what options may or may not work best, such as other health problems.

What is the process of choosing the best treatment for your situation?

Choosing the best treatment for your situation is a decision that needs to be made after all information has been shared with you, and after you’ve had time to ask questions and have them answered. This process is called informed consent and allows people to play an active role in making decisions that affect their health.

How does cancer care team determine treatment options?

How your cancer care team determines your treatment options. Depending on the type of cancer, you might have a very limited number of treatment options, or you might have many. Your cancer care team uses established treatment guidelines to figure out what treatments should be offered to you. These treatment guidelines are based on research ...

What are the options for cancer patients?

There are other options to help someone with cancer, too, These include: Palliative care: Palliative care can help any person with a serious illness, such as cancer.

How to find out about cancer treatment?

But, there’s lots of information about cancer treatments available from other sources, too. There’s also a lot of misinformation out there. You might find out information on the internet, by talking with family and friends, by going to a support group, or even by watching TV. It’s very important to be careful about where you’re getting information. Pay attention to who is sponsoring the website or advertisement, or who is giving the information you find or hear.

What is clinical trial?

A clinical trial is a research study that tests treatments on people. Sometimes these are new treatments that are being studied for the first time. Sometimes a clinical trial uses a treatment that’s already approved for a certain type of cancer and tests it on a different type of cancer.

How to write down your cancer questions?

Your doctor and cancer care team know your situation best. Write down your questions as you think of them. Bring any and all questions to your cancer care team. Write down the answers you’re given.

Why is it important to engage patients in decision making?

Patients who participate in their decisions report higher levels of satisfaction with their care ; have increased knowledge about conditions, tests, and treatment; have more realistic expectations about benefits and harms; are more likely to adhere to screening, diagnostic, or treatment plans; have reduced decisional conflict and anxiety; are less likely to receive tests or procedures which may be unnecessary; and, in some cases, even have improved health outcomes [ 60, 61, 77 ].

What are some examples of medical decisions?

Common examples of medical decisions include whether and how to make a health behavior changes, when to start and how to get preventive screening, management for acute or chronic conditions, how to prioritize competing health needs, and even when to change or stop a treatment . Some decisions are routine and occur frequently in practice such as when to start screening for breast cancer or how to be tested for colorectal cancer [ 7, 63, 75, 76 ]. In one US primary care setting, nearly one in five patients seen for an office visit faced a routine decision about preventive care [ 43 ]. Other more major decisions, such as how to treat localized breast cancer or manage an abdominal aortic aneurysm, may only occur once in a patient’s lifetime.

Why is information important to health care?

Information is central to a patient being engaged in their decisions, care, and self-management. With the advent of the internet, mobile technologies, and increasingly powerful search engines, patients can now instantaneously access all kinds of information anywhere they like to help guide their health with the touch of a button. Some patients still rely solely on the receipt of health information from clinicians, yet many more use a combination of approaches. Receiving information from a trusted clinician can be good – it can prevent a patient from being misled by inaccurate or commercially biased information. However, not actively seeking health information can be a missed opportunity. Many local and national organizations are working to raise awareness on the power of health information by promoting the need to get informed, directing patients to health information, and even creating information, ranging from educational material about health to reports on the quality of care from hospitals and clinicians to interactive and personalized tools to manage daily activities.

How does patient engagement affect health?

In other words, health and wellbeing are fostered by engaged and activated patients, who collaborate with their clinician to better manage care. In summarizing the hypothetical impact of widespread patient engagement on contemporary health care, Kish described the influence would be analogous to the introduction of a once-in-a-century blockbuster drug [ 38 ].

How can decision aids be effective?

Krist proposes that to be effective, decision aids must also be integrated into the clinical workflow – realistically, patients undergo a “decision journey [ 43 ].” This journey requires support over time, allowing patients to contemplate options, gather additional information, confer with family and friends, consider individual preferences, and address their personal worries or concerns. Clinicians can serve as trusted advisors during this decision journey. One example of systematically supporting decision journeys is how a group of practices used their patient portal to promote cancer screening decisions ( Fig. 1 ). The system anticipated the patients’ decision needs; delivered decision support prior to visits; allowed patients to tailor decision supports to their interests and needs; collected patient-reported information about where they were with their decision journey, what they wanted to discuss with their clinician, and their fears; shared the patient reported information with their clinician; set a decision-making agenda; and even provided follow-up on next steps [ 43 ]. Routine implementation of similar workflows and processes, whether technology-based or not, has great potential to improve care, address health literacy issues, and better engage patients in decision-making.

How to improve patient engagement?

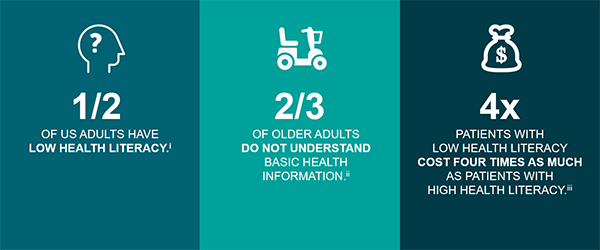

A review of proven strategies to enhance patient engagement identified three focus areas for engagement: improving health literacy, helping patients make appropriate health decisions, and improving the quality of care processes [ 16 ]. The Health Literate Care Model is an important tool to inform how attention to health literacy can improve patient engagement [ 39 ]. This model encourages clinicians to approach “all patients with the assumption that they are at risk of not understanding their health conditions or how to deal with them, and then subsequently confirming and ensuring patients’ understanding.” Across the spectrum of healthcare delivery, full engagement of the patient requires the patient to be able to obtain, process and communicate health information. Strategies to ensure that engagement activities are appropriate for a patient’s health literacy can include adapting and simplifying language to decrease the risk of misunderstanding, providing examples that are relevant to the individual’s lifestyle and cultural context, using visual representations of data, and integrating decision aids into care [ 22 ]. In a health literate care model, information needs to be presented in a manner that is congruent with a patient’s ability to understand the material and span the domains in which health care occurs – the clinical setting, home, and community.

What are the elements of informed decision making?

Braddock defined seven elements that informed decision-making: (1) discussion of the patients role in decision making, (2) discussion of the clinical issue, (3) discussion of alternatives, (4) discussion of the pros and cons of alternatives, (5) discussion of uncertainties, (6) assessment of patient understanding, and (7) exploration of patient preference [ 9 ]. Braddock acknowledged that medical decisions vary in complexity and these elements will be employed to varying degrees depending on how straight forward or complex the decision. Embedded in each element is a recognition that in order for a patient to fully engage in any discussion there is need for the patient to have some health literacy. Clinicians should approach decision steps with attention to the patient’s literacy needs and assess the patient’s knowledge and understanding throughout.

What are the two components of treatment decisions?

w12-w14 Deber suggested there may be two components of treatment decisions—problem solving (“identifying the one right answer”) and decision making (“selecting the most desired bundle of outcomes”) —and hypothesised that, whereas patients may prefer doctors to perform the problem solving component (which requires clinical expertise), patients would want to be involved in decision making . 13 This was supported in a survey of patients undergoing angiography. w15

Why do patients need to be given technical information that is clear and unbiased?

Patients must be given technical information that is clear and unbiased to ensure that their preferences are based on fact and not misconception.

Why should doctors understand patients' preferences?

To improve the quality of care they provide , doctors should understand their patients' preferences. However, this raises many challenges for doctors. Practical concerns include time pressures and difficulties in eliciting preferences from patients who may be hesitant to make treatment decisions.

What is the Medicines Partnership?

Medicines Partnership ( www.concordance.org/ ).Two year initiative supported by the Department of Health aimed at putting the principles of concordance into practice, including professional development, projects, research, health policy, and information for and from patients and the public

Why is it important to understand risks?

Enabling patients to understand risks is crucial before considering different treatment options. Yet risk is a complex phenomenon that many patients (and doctors) find difficult to understand. Common errors include compression bias (the tendency to overestimate small risks and underestimate large ones), miscalibration bias (overestimation of the level and accuracy of one's knowledge), availability bias (overestimation of notorious risks 20 ), and optimism-pessimism bias (the tendency of patients to believe that they are at less risk of an adverse outcome than people similar to them 14 ).

Is Decision Analysis used in clinical practice?

Decision analysis may facilitate communication of complex risks. w23 However, it has not yet been routinely used in clinical practice, and methodological limitations, such as only expressing outcomes in numerical terms, may limit its usefulness. w23

Do doctors have the appropriate competences?

Doctors may not have the appropriate competences, with risk communication particularly challenging, and patients' preferences may differ from those of their doctors or evidence based guidelines

Why is patient participation important in decision making?

One huge advantage to patient participation in the decision-making process is that they are more likely to be compliant with the treatment plan. The best recommendation is wasted if the patient does not follow it.

What is patient centered decision making?

“Patient-Centered” decision-making is a new buzz-word in medicine. It is a metaphor for a general approach to care that puts the patient’s experience and needs at the center, as opposed to the needs of the physician or the system.

What is optimal practice?

Optimal medical practice would maximize several outcomes simultaneously — the patient experience, doctor and patient autonomy, medical outcomes, and cost effectiveness, to name the most important. The problem is, you can’t always get all of these things to an optimal degree at the same time.

Why do patients need counseling?

Patients often need counseling if fear, anxiety, or hidden misconceptions are causing them to make decisions that depart significantly from what the evidence suggests is the best course. This, of course, all depends on what the patient’s goals are, and this is always a good place to begin (rather than assuming what their goals are).

Who is the central actor in the doctor-patient interaction?

He concludes, and I agree, that the patient and the physician are both the central actors in the doctor-patient interaction, but that there are interested third parties, like insurance companies, that also affect decision-making.

Is there a model for patient participation in decision making?

Patient participation in decision-making remains a complex question. Clearly there is no one model for all patients — patients have different desires in this regard, and varying healthcare literacy. Keep in mind, an adult competent patient is 100% in control of their own health care decision-making. The ultimate decision is always theirs. What we are talking about is how the patient and physician should interact.

Is rising costs of health care more acute?

The rising costs of health care make all of these issues much more acute. Can we afford a philosophical shift to greater patient involvement in decision-making when it is associated with higher costs and we don’t really know the net effect on medical outcomes but there is good reason to suspect that it may be negative (when compared to evidence-based standards)? It seems to me we should more thoroughly explore these outcomes before we institute major infrastructural changes.

Why is it important to discuss medical risks with patients?

Discussing these risks with patients is a fundamental duty of physicians both to fulfill a role as trusted adviser and to promote the ethical principle of autonomy (particularly as embodied in the doctrine of informed consent). Discussing medical risk is a difficult task to accomplish appropriately. Challenges stem from gaps in the physician's knowledge about pertinent risks, uncertainty about how much and what kind of information to communicate, and difficulties in communicating risk information in a format that is clearly understood by most patients. For example, a discussion of the risk of undergoing a procedure should be accompanied by a discussion of the risk of not undergoing a procedure. This article describes basic characteristics of risk information, outlines major challenges in communicating risk information, and suggests several ways to communicate risk information to patients in an understandable format. Ultimately, a combination of formats (eg, qualitative, quantitative, and graphic) may best accommodate the widely varying needs, preferences, and abilities of patients. Such communication will help the physician accomplish the fundamental duty of teaching the patient the information necessary to make an informed and appropriate decision.

What is regret in prostate cancer?

Importance Treatment-related regret is an integrative, patient-centered measure that accounts for morbidity, oncologic outcomes, and anxiety associated with prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. Objective To assess the association between treatment approach, functional outcomes, and patient expectations and treatment-related regret among patients with localized prostate cancer. Design, Setting, and Participants This population-based, prospective cohort study used 5 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–based registries in the Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation cohort. Participants included men with clinically localized prostate cancer from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012. Data were analyzed from August 2, 2020, to March 1, 2021. Exposures Prostate cancer treatments included surgery, radiotherapy, and active surveillance. Main Outcomes and Measures Patient-reported treatment-related regret using validated metrics. Regression models were adjusted for demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics, treatment approach, and patient-reported functional outcomes. Results Among the 2072 men included in the analysis (median age, 64 [IQR, 59-69] years), treatment-related regret at 5 years after diagnosis was reported in 183 patients (16%) undergoing surgery, 76 (11%) undergoing radiotherapy, and 20 (7%) undergoing active surveillance. Compared with active surveillance and adjusting for baseline differences, active treatment was associated with an increased likelihood of regret for those undergoing surgery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.40 [95% CI, 1.44-4.01]) but not radiotherapy (aOR, 1.53 [95% CI, 0.88-2.66]). When mediation by patient-reported functional outcomes was considered, treatment modality was not independently associated with regret. Sexual dysfunction, but not other patient-reported functional outcomes, was significantly associated with regret (aOR for change in sexual function from baseline, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.52-0.81]). Subjective patient-perceived treatment efficacy (aOR, 5.40 [95% CI, 2.15-13.56]) and adverse effects (aOR, 5.83 [95% CI, 3.97-8.58]), compared with patient expectations before treatment, were associated with treatment-related regret. Other patient characteristics at the time of treatment decision-making, including participatory decision-making tool scores (aOR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.69-0.92]), social support (aOR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.67-0.90]), and age (aOR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.62-0.97]), were significantly associated with regret. Results were comparable when assessing regret at 3 years rather than 5 years. Conclusions and Relevance The findings of this cohort study suggest that more than 1 in 10 patients with localized prostate cancer experience treatment-related regret. The rates of regret appear to differ between treatment approaches in a manner that is mediated by functional outcomes and patient expectations. Treatment preparedness that focuses on expectations and treatment toxicity and is delivered in the context of shared decision-making should be the subject of future research to examine whether it can reduce regret.

How many recommendations were made by the Bristol inquiry?

Many of the 198 recommendations made by the Bristol inquiry urged doctors to include patients as active participants in their own care. Angela Coulter discusses how these recommendations can be turned into realityThe public inquiry into failures in the performance of surgeons involved in heart surgery on children at the Bristol Royal Infirmary between 1984 and 1995 made 198 recommendations on how to prevent failures in the future. The pre-eminent recommendations urged doctors to:Involve patients (or their parents) in decisionsKeep patients (or parents) informedImprove communication with patients (or parents)Provide patients (or parents) with counselling and supportGain informed consent for all procedures and processesElicit feedback from patients (or parents) and listen to their viewsBe open and candid when adverse events occur.1These recommendations are fine rhetoric, but how can they be turned into reality?Improving responsiveness to patients has been a goal of health policy in the United Kingdom for several decades. Until now, most initiatives in this area have failed to change noticeably the everyday experience of most patients in the NHS. The harsh realities of budgetary pressures, staff shortages, and other managerial imperatives tend to displace good intentions about informing and involving patients, responding quickly and effectively to patients' needs and wishes, and ensuring that patients are treated in a dignified and supportive manner. This is the essence of patient centred care, and most health professionals strive to achieve it. Many clinical staff, however, feel that demands for them to improve efficiency and productivity have restricted their ability to offer the time and empathy that patients need and hope for.2Summary pointsThe Bristol inquiry recommended that patients must be at the centre of the NHS and must be treated as partners by health professionals—as “equals with different expertise”The survival of the NHS depends on the extent to which it can improve responsiveness to patients' needs and wishesAppropriateness and outcome of care can be improved by engaging patients in treatment and management decisionsSafety could be improved and complaints and litigation reduced if patients were actively involved in their own careRegular, systematic feedback from patients is essential to improve quality of care and for public accountabilityA new urgency is in the air, though—improving patients' experiences is much higher up the agenda. In 2000 the British government made this the central theme of its plan for the NHS. It announced that incentive systems would be realigned to encourage improvements in performance and that patients' feedback would be incorporated into the star rating system for performance indicators.3 This carrot and stick approach may be needed to kick start the move towards greater responsiveness to patients, but deeper reasons lie behind the need for healthcare providers to move in this direction.Why do we need greater responsiveness to patients?Meeting expectationsThat public expectations are rising faster than the ability of health services to meet them is now a cliché. This fact describes, however, one of the most important ironies of modern health care. Public spending on health care is increasing much faster than inflation in most countries, and effective treatments are available more widely than ever before. At the same time, public pessimism about the future of health systems is growing.4 Although patients' overall satisfaction with the NHS has fluctuated in recent years, inpatients' satisfaction with hospital care has been decreasing since 1989.5The British public continues to strongly support the principle that health care should be funded by taxes. Memories of the fragmented and inequitable system that preceded its introduction are fading, however, and the NHS can no longer trade on people's gratitude. Tolerance of long waiting times, lack of information, uncommunicative staff, and failures to seek patients' views and take account of their preferences is wearing thin. Politicians recognise this—hence their goal of modernising the system by encouraging greater responsiveness to patients. In the long run, the survival of the NHS depends on the extent to which this goal can be achieved.Providing appropriate careProvision of information to and involvement of the patient is at the heart of the patient centred approach to health care. If doctors are ignorant of patients' values and preferences, patients may receive treatment that is inappropriate to their needs. Studies have shown that doctors often fail to understand patients' preferences.6 The quality of clinical communication is related to positive health outcomes.7 Patients who are well informed about prognosis and treatment options, including potential harms and side effects, are more likely to adhere to treatments and have better health outcomes.8 They are also less likely to accept ineffective or risky procedures.9 To maximise the benefit of treatment, doctors need to give patients clear explanations of the nature of clinical evidence and its interpretation.Evidence supports the shift towards shared decision making, in which patients are encouraged to express their views and participate in making clinical decisions. The key to successful doctor-patient partnerships is to recognise that patients are also experts. Doctors are—or should be—well informed about diagnostic techniques, the causes of disease, prognosis, treatment options, and preventive strategies. But only patients know about their experience of illness and their social circumstances, habits, behaviour, attitudes to risk, values, and preferences. Both types of knowledge are needed to manage illnesses successfully, and the two parties must be prepared to share information and make joint decisions, drawing on a sound base of evidence. Studies of general practice consultations in the United Kingdom found little evidence that doctors and patients currently share decision making in the recommended manner. 10 11 Interest in this approach is growing among clinicians, however, particularly among those involved in primary care. Training is now required to equip doctors with the communication skills needed to help patients play a more active role.12Ensuring patient safetyDoctors could reduce the incidence of medical errors and adverse events by actively involving patients. Patients who know what to expect in relation to quality standards can check on the appropriate performance of clinical tasks. For example, prescribing errors are relatively common (box 1),13 but many might be avoided if patients were more actively engaged in their own care. Better design of drug information leaflets and drug packaging could help too—patients should be involved in reviewing and redesigning these.14Box 1: Relatively common prescribing errorsPoor compliance caused by prescribers failing to elicit patients' preferences and beliefs about medicinesPoor compliance caused by prescribers failing to explain why a drug is being prescribed and how it is supposed to workInappropriate drugs or dosages caused by poor communication between doctors about contraindications or adverse reactionsFailure to convey essential information to patients about how and when to take their drugsFailure to discuss common side effects, so that patients are ill prepared to cope with these and to recognise unexpected problemsErrors resulting from problems occurring when medical records are transcribed (these could be avoided if patients were encouraged to check their notes)Patients should be encouraged to review their notes, including referral letters and test results. In its plan for the NHS, the British government announced its intention to give all patients access to their electronic health records by 2004. Electronic access has the potential to significantly improve communication and accuracy of records, but a daunting number of technical and cultural barriers need to be overcome before this goal can be achieved. The scheme is currently being piloted in general practice as part of the electronic record development and implementation programme.15 A feasibility study found that patients like the idea of electronic access.Reducing complaints and litigationPoor communication and failure to take account of the patient's perspective are at the heart of most formal complaints and legal actions. Error rates could be reduced by an approach that is more patient centred; such an approach could also do much to ameliorate the adverse effects of errors if they do occur. A survey of 227 litigants who sued healthcare providers found that the overwhelming majority were dissatisfied with the nature and clarity of the explanations they were given and the lack of sympathy displayed by staff after the incident.16 In some cases, litigation might have been avoided altogether if staff had dealt with patients more sensitively after the incident.Procedures used to gain informed consent often fall short of the ideal. Many involve a hasty discussion between a patient and a junior doctor, whose sole aim is to get a signature on a form. Options and alternatives are rarely discussed with the patient (or parent), and the “consent” implied by the signature cannot be said to be truly informed.17 Doctors who fail to provide full and balanced information about the risks and uncertainties of procedures and treatments can create unrealistic expectations; these may be the reason for the United Kingdom's rising rates of litigation. Patients are often given a biased and highly optimistic picture of the benefits of medical care.18 For patients encouraged to believe that there is an effective pill for every illness or that surgery is free of risk, it is no wonder that the reality is often disappointing. Misplaced paternalism that tries to “protect” patients from the bad news merely fuels false hopes and does no one—patient or clinician—any good in the long run.Encouraging self relianceThe paternalistic manner in which health care is currently delivered tends to foster demand, instead of encouraging self reliance. All too often patients are treated like children who need to be told what to do and to be reassured, rather than as responsible adults capable of assimilating information and using it to make informed choices. Paternalism fosters passivity and dependence, saps self confidence, and undermines people's ability to cope. Instead of treating patients as passive recipients of medical care, it is much more appropriate to view them as partners or coproducers.19 Their input is essential to defining and understanding the problem, identifying possible solutions, and managing the illness.Patients who are to be treated as coproducers need to be given the tools for the job. When patients are provided with unbiased, evidence based information about treatment options, likely outcomes, and self care, they usually make rational choices that are often more conservative and involve less risk than their doctors would choose.20 For example, American patients given full information about the pros and cons of screening for prostate specific antigen to detect prostate cancer were less likely to undergo the test than those who were not fully informed.9 Appropriate and cost effective use of health services could be encouraged by investing in tools to help patients make evidence based decisions.21 These decision aids must be provided by reliable, independent sources that the public trust. Some public funding will be necessary—the pharmaceutical industry should not be left to make all the running.View larger version:In a new windowDownload as PowerPoint SlidePercentage of 84 500 patients with coronary heart disease who did not feel sufficiently involved in decisions about their care. Data from National Surveys of NHS Patients. Coronary Heart Disease 1999Box 2: Tools to empower patientsRecognise patients' expertise, values, and preferencesOffer informed choice, not passive consentTraining in shared decision makingEvidence based decision aids for patientsPublic education on interpreting clinical evidencePatient access to electronic health recordsSurveys of patients' experience to prioritise quality improvementsOpenness and empathy with patients (or parents) after medical errors have occurredPublic access to comparative data on quality and outcomesQuality improvementIf we want to centre quality improvement efforts on the needs and wishes of patients, we must first understand how things look through their eyes, and those of their carers. Healthcare providers have measured patients' satisfaction for many years. Often, however, these surveys have been conceptually flawed and methodologically weak, with the focus on managers' agendas rather than the topics most important to patients.22A more valid approach is to ask patients to report in detail on their experiences by asking them specific questions about whether or not certain processes and events occurred during a specific episode of care.23 From December 2001, a new programme of surveys in NHS trusts has adopted this approach. Systematic feedback from patients, gained with high quality surveys, will generate information that is more pertinent to patients and healthcare providers at the front line than existing data systems. The success of these surveys will depend on how willing healthcare providers are to use the results to introduce initiatives to improve quality.Public accountabilityThe high cost of health care and its demands on the public purse have led to calls for healthcare facilities to be more accountable to the public. This demand has resulted in the publication of performance indicators that allow healthcare facilities to be compared. These performance indicators are intended to provide information to be used to determine priorities for quality improvements as well as a detailed account of how public funds have been used.Public access to data on the quality of care among different healthcare providers has developed much further in the United States and Canada than in the United Kingdom. However, hospital report cards and physician profiles are now being promoted in the United Kingdom. Commercial websites, such as Dr Foster (home.drfoster.co.uk), encourage the public to seek and use systematic information on the quality of health care. The establishment of new mechanisms to promote choice and accountability—such as the requirement that each hospital and primary care trust publishes a prospectus for patients—will further boost these efforts. This strategy is not without risks, not least that providers will find ways of “gaming” the system to make their performance look better than it actually is. It is by no means inevitable that the trend towards public disclosure will encourage providers to refocus their efforts on quality improvement.24SummaryThe lessons learned in the Bristol inquiry were clearly stated in the report. The changes demanded were well founded and are achievable. What is needed now is clear leadership from the clinical professions, investment in information and training, and a willingness to change established modes of working (box 2).AcknowledgmentsThis is a revised version of a paper presented at a conference on improving quality of health care in the United States and United Kingdom on 22-24 June 2001, which was cosponsored by the Commonwealth Fund and the Nuffield Trust.FootnotesFunding None.Competing interests AC contributed to one of the seminars of the Bristol inquiry. Picker Institute Europe organises patient feedback surveys for NHS trusts.References1.↵Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. Learning from Bristol: the report of the public inquiry into children's heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. London: Stationery Office, 2001. http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/ (accessed 5 Feb 2001).2.↵Mercer SW, Watt GCM, Reilly D. Empathy is important for enablement. BMJ 2001; 322: 865.OpenUrlFREE Full Text3.↵Secretary of State for Health. The NHS plan. London: Stationery Office, 2000.4.↵Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Schoen C, Binns K, Osborn R, Davis K. The elderly in five nations: the importance of universal coverage. Health Affairs 2000; 19: 226–235.OpenUrlFREE Full Text5.↵Mulligan J. What do the public think? London: Health Care UK and King's Fund, 2000: 12–17.6.↵Cockburn J, Pit S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients' expectations and doctors' perceptions of patients' expectations. BMJ 1997; 315: 520–523.OpenUrlFREE Full Text7.↵Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2001; 357: 757–762.OpenUrlCrossRefMedlineWeb of Science8.↵Mullen PD. Compliance becomes concordance. BMJ 1997; 314: 691.OpenUrlFREE Full Text9.↵Volk RJ, Cass AR, Spann SJ. A randomized controlled trial of shared decision making for prostate cancer screening. Arch Fam Med 1999; 8: 333–340.OpenUrlFREE Full Text10.↵Makoul G, Arntson P, Schofield T. Health promotion in primary care: physician-patient communication and decision-making about prescription medications. Soc Sci Med 1995; 41: 1241–1254.11.↵Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley CP. Doctor-patient communication about drugs: the evidence for shared decision making. Soc Sci Med 2000; 50: 829–840.12.↵Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50: 892–897.OpenUrlMedlineWeb of Science13.↵Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Q Health Care 2000; 9: 232–237.OpenUrlFREE Full Text14.↵Consumers' Association. Patient information leaflets: sick notes? London: Consumers' Association, 2000.15.↵Pyper C, Amery J, Watson M, Crook C, Thomas B. ERDIP online patient access project. Oxford: Bury Knowle Health Centre and Department of Public Health, University of Oxford, 2001.16.↵Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet 1994; 343: 1609–1613.OpenUrlCrossRefMedlineWeb of Science17.↵Lavelle-Jones C, Byrne DJ, Rice P, Cuschieri A. Factors affecting quality of informed consent. BMJ 1993; 306: 885–890.18.↵Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ 1999; 318: 318–322.OpenUrlFREE Full Text19.↵Tudor Hart J. Expectations of health care: promoted, managed or shared? Health Expectations 1998; 1: 3–13.OpenUrlCrossRefMedline20.↵O'Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, Tetroe J, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ 1999; 319: 731–734.OpenUrlFREE Full Text21.↵Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Entwistle V, Coulter A, O'Connor A, Rovner DR. Patient choice modules for summaries of clinical effectiveness: a proposal. BMJ 2001; 322: 664–667.OpenUrlFREE Full Text22.↵Sitzia J, Wood J. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 1829–1843.23.↵Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S. Health care quality: incorporating consumer perspectives. JAMA 1997; 278: 1608–1612.OpenUrlFREE Full Text24.↵Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA 2000; 282: 1866–1874.OpenUrlCommentary: Patient centred care: timely, but is it practical?Nick Dunn, senior lecturer in primary medical care (nick.dunn {at}soton.ac.uk)Picker Institute Europe, Oxford OX1 1RXSchool of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton SO16 5STProfessor Ian Kennedy's report on children's heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary is 530 pages long and contains 27 pages of recommendations1; the second half of the report refers to all healthcare professionals in the NHS. The report is not easy reading, in terms of either its volume or its content. Angela Coulter has done us all a favour by emphasising one of the main themes of the report in an easily digestible form.Patient centredness is not a new concept: Balint was talking about it nearly 50 years ago.2 The concept has achieved a new urgency, however, partly because of rising levels of patients' dissatisfaction with the NHS and consequent medicolegal implications—of which Bristol is only one example—and partly because patient opinion has been seen as a potential lever for general quality improvement.3 The goal is to make patients and healthcare professionals equal partners in making clinical decisions. But, is this goal desirable or achievable?One major obstacle is lack of time. Coulter does not discuss this, and there is scant discussion in a few paragraphs of the Bristol report, which ends: “NHS trusts must make sure that the working arrangements of healthcare professionals allow them the necessary time to communicate with patients.” Surely an indisputable truth, but how is it to be done? The average time for general practitioners' consultations is about eight minutes, and hospital consultations often are equally short. This brevity is not predominantly a matter of choice, but is due to circumstances. Towle suggests that “competence” in shared decision making can be shown in a 10 minute encounter,4 but the time taken to reach meaningful decision sharing will depend very much on the background of patients, their level of intelligence, and the condition under discussion. In many cases, 10 minutes would allow only an introduction to the problem.Do all patients want to participate in shared decision making? Probably not. Elderly patients have often been used to, and like, a paternalistic approach. Younger patients may favour more open discussion, but this is not inevitable. The doctor's knowledge of the patient is vital here, and many general practitioners would favour keeping consultations involving shared decisions as “a tool I keep in my back pocket.”The need for up to date, relevant information for patients and healthcare workers is vital, and Coulter rightly points out the need to have a sound, and accessible, base of evidence. This is partly a matter for education and training of healthcare professionals, and partly a need for well designed and understandable leaflets to provide information to patients. The use of software to support clinical decisions deserves to be more widespread. The evidence base for patients will, of course, need to be updated continually, and healthcare professionals will need to update themselves as well—or else risk talking at cross purposes with the patient.Coulter's (and Professor Kennedy's) call for patient centred care is timely, and the case for such an approach is strong. However, consultation style cannot be imposed on either professional or patient, and patient centredness is not a cheap option, in terms of either staffing time or resources.AcknowledgmentsCompeting interests: None declared.References1.↵Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. Learning from Bristol: the report of the public inquiry into children's heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. London: Stationery Office, 2001. http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/ (accessed 5 Feb 2001).2.↵Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. In: London: Tavistock Publications, 1957.3.↵Cleary PD. The increasing importance of patient surveys. BMJ 1999; 319: 720–721.OpenUrlFREE Full Text4.↵Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ 1999; 319: 766–761.OpenUrlFREE Full Text

Do doctors have to be informed about their diagnosis?

Doctors are—or should be—well informed about diagnostic techniques, the causes of disease, prognosis, treatment options, and preventive strategies. But only patients know about their experience of illness and their social circumstances, habits, behaviour, attitudes to risk, values, and preferences.

Does fan therapy help with COPD?

Background Patients with COPD reduce physical activity to avoid the onset of breathlessness. Fan therapy can reduce breathlessness at rest, but the efficacy of fan therapy during exercise remains unknown in this population. The aim of the present study was to investigate 1) the effect of fan therapy on exercise-induced breathlessness and post-exercise recovery time in patients with COPD and 2) the acceptability of fan therapy during exercise; and 3) to assess the reproducibility of any observed improvements in outcome measures. Methods A pilot single-centre, randomised, controlled, crossover open (nonmasked) trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03137524 ) of fan therapy versus no fan therapy during 6-min walk test (6MWT) in patients with COPD and a modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea score ≥2. Breathlessness intensity was quantified before and on termination of the 6MWT, using the numerical rating scale (NRS) (0–10). Post-exertional recovery time was measured, defined as the time taken to return to baseline NRS breathlessness score. Oxygen saturation and heart rate were measure pre- and post-6MWT. Results 14 patients with COPD completed the trial per protocol (four male, 10 female; median (interquartile range (IQR)) age 66.50 (60.75 to 73.50) years); mMRC dyspnoea 3 (2 to 3)). Fan therapy resulted in lower exercise-induced breathlessness (ΔNRS; Δ modified Borg scale) (within-individual differences in medians (WIDiM) −1.00, IQR −2.00 to −0.50; p<0.01; WIDiM −0.25, IQR −2.00 to 0.00; p=0.02), greater distance walked (metres) during the 6MWT (WIDiM 21.25, IQR 12.75 to 31.88; p<0.01), and improved post-exertional breathlessness (NRS) recovery time (WIDiM −10.00, IQR −78.75 to 50.00; p<0.01). Fan therapy was deemed to be acceptable by 92% of participants. Conclusion Fan therapy was acceptable and provided symptomatic relief to patients with COPD during exercise. These data will inform larger pilot studies and efficacy studies of fan therapy during exercise.

How can physicians engage patients in decision making?

Physicians can engage patients about decision-making in ways that are inclusive of family input, and help consider possible roles of surrogate decision-makers for patients who do not have decision-making capacity.

What is the importance of discussing a patient's case together?

Minimize confusion. A patient’s care is often divided among multiple clinicians, so it is essential for them to discuss the case together. This doesn't mean making decisions for the patient. Rather, this means achieving professional consensus about the options and their corresponding risks and benefits so that family members receive consistent information from caregivers about potential next steps.

What is patient autonomy?

Patient autonomy has traditionally been one of the most prominent principles of American medical ethics, but often patients don’t make decisions about their care alone. Some choose to involve family members, even sometimes allowing the family’s desires to supersede their own. Respecting autonomy necessarily means respecting patients’ decisions.

How to encourage patients to share their hopes?

Encourage the patient to be open. Remind patients that their family members might be more open to their desired care options than they think, and encourage patients to share their hopes.

How to help family members at end of life?

Help everyone identify their values. Studies show patients’ values and those of their family members are often closely aligned, so facilitating a discussion about goals and values— especially independence—can generate consensus. In the case of end-of-life situations , this can help family members understand and respect each other’s perspectives.