At first, the answer appeared to be that cardiometabolic risk because of genetics and environment comes first, and any cardiometabolic risk associated with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment was originally obscured.

How do antipsychotics differ in their cardio-metabolic risk?

Results: Strong evidence exists for significant cardiometabolic risk differences among several antipsychotic agents. Histamine H1 and serotonin 5HT2C antagonism are associated with risk of weight gain, but receptor targets for dyslipidemia and insulin resistance have not yet been identified. Convincing data indicate that hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance may occur …

What do European psychiatrists think about cardiometabolic risk factors in schizophrenia?

Because atypical antipsychotics are frequently administered to the very patients who have increased genetic and lifestyle risks of cardiometabolic illness and premature death , this has led to the question: which comes first, atypical antipsychotic treatment or cardiometabolic risk? At first, the answer appeared to be that cardiometabolic risk because of genetics and …

What types of patients with schizophrenia are free from antipsychotics?

Conclusion: Although lifestyle and genetics may contribute independent risks of cardiometabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia and other serious mental illness, antipsychotic treatment also represents an important contributor to risk of cardiometabolic dysfunction, particularly for certain drugs and for vulnerable patients. Mental health professionals must learn to recognize the …

Are atypical antipsychotics the first-line of treatment?

Why atypical antipsychotic drugs are the most preferred now to be used clinically compared to typical antipsychotic drugs?

Why would a doctor prefer an atypical antipsychotic over a first generation antipsychotic?

What was the first atypical antipsychotic to be developed Why is it not considered a first-line treatment for schizophrenia?

What is the main advantage of atypical antipsychotics over typical antipsychotics?

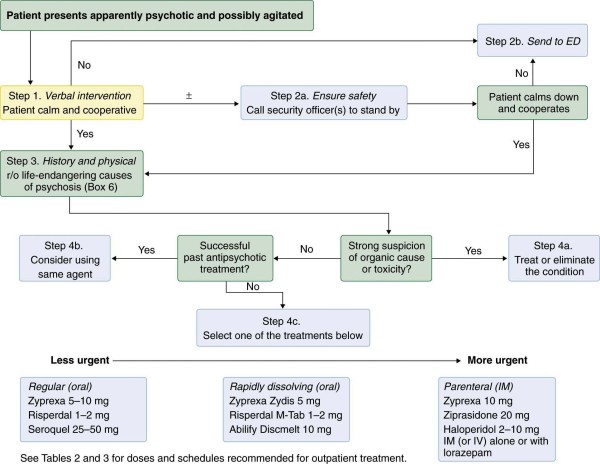

When do you use atypical antipsychotics?

What do first-generation antipsychotics treat?

What do first-generation antipsychotics do?

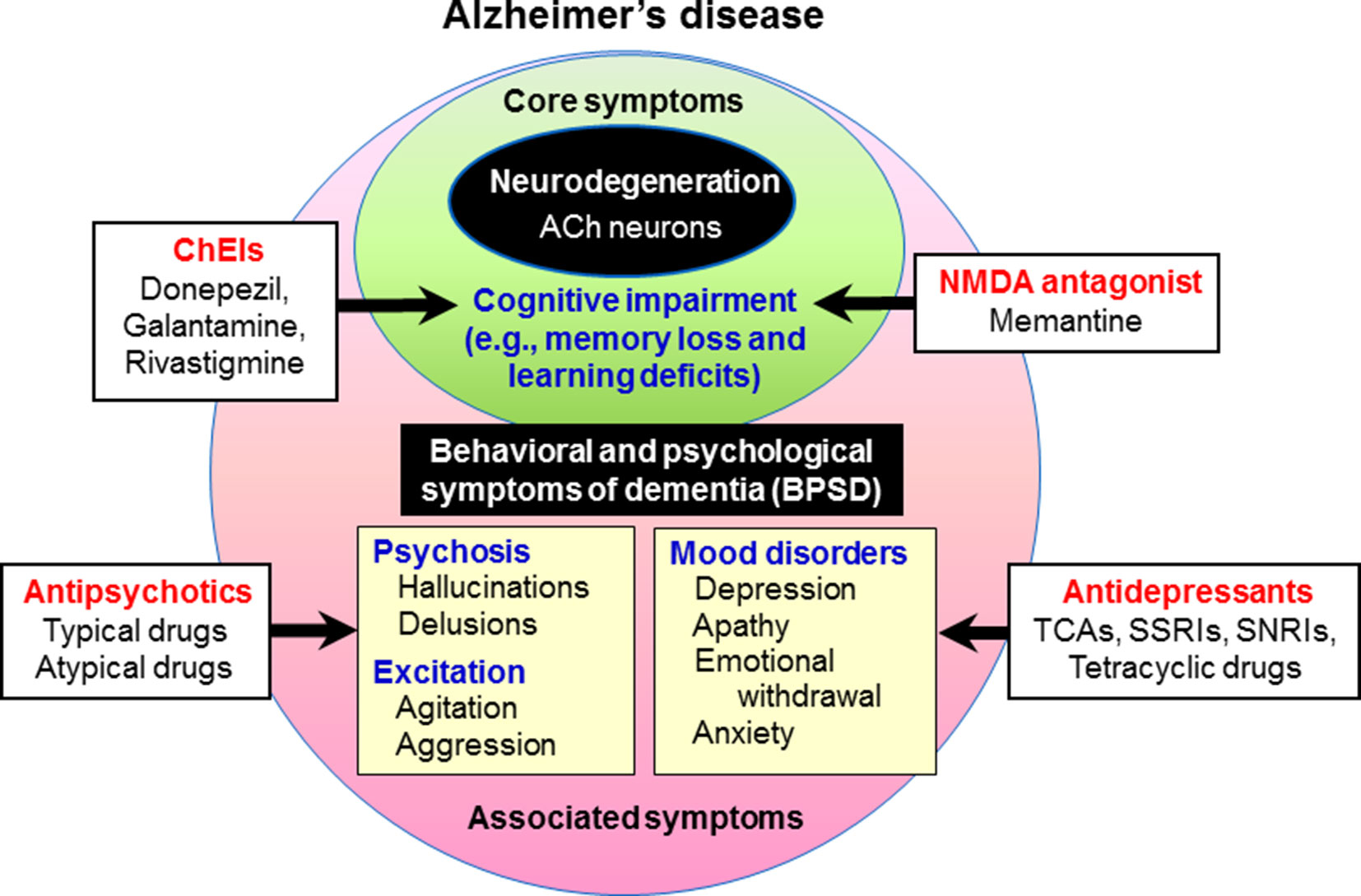

What do atypical antipsychotics treat?

What was the first atypical antipsychotic?

What is the first-line treatment for schizophrenia?

What is the first-line drug treatment for schizophrenia?

What are the risks of taking atypical antipsychotics?

Atypical antipsychotics can lead to cardiometabolic risk , from weight gain and obesity to hypertriglyceridemia and DKA/HHS. It is thus clearly necessary to determine where any patient receiving an antipsychotic drug falls along this metabolic highway, and to monitor such patients cautiously and continuously once an antipsychotic is initiated ( Fig. 4 ). To prevent patients from further sliding down the ‘slippery slope’ to a cascade of cardiometabolic events potentially ending in premature death, clinicians should obtain a family history of diabetes, monitor weight gain and BMI, and measure fasting triglyceride levels before and after initiation of an atypical antipsychotic to determine whether dyslipidemia and increased insulin resistance are developing ( 6 ). The best practices are to monitor these parameters in anyone taking atypical antipsychotics as discussed in the accompanying paper ( 9 ). Additionally, a significant increase in BMI or fasting triglyceride levels might require a switch to a different, less ‘threatening’ antipsychotic. It is especially important to monitor blood pressure, fasting glucose and waist circumference before and after initiating an atypical antipsychotic, in patients who are obese, with dyslipidemia, and either in a prediabetic or diabetic state. High-risk patients, who present with pending or actual pancreatic beta-cell failure as manifested by hyperinsulinemia, prediabetes or diabetes, may need to be put on an antipsychotic with a low cardiometabolic risk and should be cautiously monitored to detect early signs of the rare but potentially life-threatening DKA/HHS. In general, the best possible metabolic outcome will be reached by choosing the least metabolically impairing atypical antipsychotic for that individual patient ( 47 ). One can only know that by monitoring the cardiometabolic status of each patient individually. While clinicians who prescribe antipsychotics do not need to be endocrinologists, they should be savvy about establishing monitoring parameters especially when initiating or switching atypical antipsychotics.

What is the primary aim of this clinical overview article?

The primary aim of this clinical overview article was to discuss the impact that atypical antipsychotics have on cardiometabolic risk in patients with schizophrenia. The secondary aim of the current paper was to give a pharmacological rationale as to why these drugs have the potential to induce cardiometabolic side effects in a wide variety of patients. A companion article in this series of ‘Clinical Overview’ has already provided a comprehensive summary of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia and of the treatment approaches and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in these patients ( 9 ).

Do antipsychotics cause weight gain?

While conventional antipsychotics might also lead to weight gain, especially the less frequently used low-potency convention al antipsychotics ( 3, 4 ), certain atypical antipsychotics are now known to induce much greater weight gain and cardiometabolic changes in certain patients, by mechanisms that remain to be elucidated ( 3 - 6 ). Given the widespread use of atypical antipsychotics, and the burgeoning literature on cardiometabolic effects of antipsychotics, this article will focus on the differential contributions of various atypical antipsychotics to weight gain, dyslipidemia and glycemic disturbances ( Table 1 ), and will summarize evidence for adiposity-independent effects on dyslipidemia and diabetes risk ( 2, 7, 8) ( Table 2 ). A companion article ( 9) provides a clinical overview of the role of schizophrenia itself as a risk factor for cardiometabolic risk and also discusses how to monitor and treat patients for this risk.

Can antipsychotics increase fasting triglycerides?

The mechanism of increased insulin resistance and the consequent elevation of fasting triglycerides by some atypical antipsychotics have been vigorously pursued ( 35 ), but have not yet been identified. Some antipsychotics can lead to a rapid elevation of fasting triglycerides upon initiation of treatment ( 39) and a rapid fall of fasting triglycerides upon discontinuation of treatment ( 40 ), suggesting that a yet unidentified pharmacological mechanism is responsible for these rapid changes. One hypothesis posits that some antipsychotics could bind to a receptor ‘X’ on adipose tissue, liver and skeletal muscle – and possibly the brain – which would lead to insulin resistance, at least in certain patients ( Fig. 5 ). Thus, in some patients, the entrance ramp leading them onto the ‘metabolic highway’ would be the ability of certain antipsychotics to significantly increase fasting plasma triglyceride levels and the resulting insulin resistance ( Fig. 1 ). This would bring these patients to the next step down the slippery slope towards cardiometabolic risk ( Fig. 4 ). Not all patients will develop this problem on all antipsychotics, but certain agents appear to have much higher risk. Nonetheless, a safety net should be in place to monitor all patients on atypical antipsychotics in order to catch the ones who will develop these adiposity-independent effects. That safety net should at a minimum be the regular monitoring of fasting triglycerides, weight and BMI, if not other elements associated with the ‘metabolic syndrome’ such as fasting glucose, blood pressure and other lipids.

What is a second generation antipsychotic?

Background: Second generation antipsychotic medications (SGAs) are widely used by reproductive-age women to treat a number of psychiatric illnesses. Some SGAs have been associated with an increased risk of developing diabetes, although information regarding their diabetogenic effect in pregnant women is scarce. Objective: To evaluate the risk of gestational diabetes (GDM) among women treated with SGA. Method: The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) collects data on drug use, pregnancy outcomes, and other characteristics from pregnant women, ages 18-45 years, using 3 phone interviews conducted at (1) enrollment during pregnancy, (2) 7 months' gestation, and (3) 2-3 months postpartum. Information on GDM was abstracted from obstetric and delivery medical records. The study population was restricted to women without pre-gestational diabetes. Pregnancies exposed to SGAs during the first trimester were compared with a reference group of women with psychiatric conditions but not treated with SGAs during pregnancy. Generalized linear models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for GDM. Results: Of 303 women exposed to SGAs, 33 (10.9%) had GDM compared to 16 (10.7%) in the 149 non-exposed women. The crude OR of GDM for SGA was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.54-1.91). After adjustment for maternal age, race, marital status, employment status, level of education, smoking, and primary psychiatric diagnosis, the OR moved to 0.79 (0.40-1.56). Conclusions: Findings did not suggest an increased risk of GDM associated with exposure to SGAs during pregnancy in women who had used SGA before pregnancy without developing diabetes, compared to psychiatrically ill women who were not exposed to SGA. Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01246765.o Full text: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022395617306386

What is the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk?

The information on prevalence of obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome (MetS) and cardiovascular risk (CVR) and on sociodemographic variables available in patients with psychiatric diseases about to be treated with weight gain-associated medication (e.g., clozapine, mirtazapine, quetiapine) is limited. In a naturalistic study, psychiatric inpatients (age: 18–75) of all F diagnoses according to ICD-10, who were about to be treated with weight gain-associated medication, were included. Demographic variables were assessed as well as biological parameters to calculate the Body Mass Index (BMI), MetS, diabetes and CVR. A total of 163 inpatients were included (60.1% male; mean age: 39.8 (± 15.1, 18–75 years). The three most common disorders were depression (46.0%), bipolar disorder (20.9%) and drug addiction (20.2%). The three most common pharmacotherapeutic agents prescribed were quetiapine (29.4%), mirtazapine (20.9%) and risperidone (12.9%). Of the included inpatients 30.1% were overweight, 17.2% obese, and 26.9% and 22.4% fulfilled the criteria for a MetS according to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the National Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (NCEP ATP III), respectively, 3.8% had (pre)diabetes and 8.3% had a moderate and 1.9% a high CVR according to the Prospective Cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM) score. Detailed information is reported on all assessed parameters as well as on subgroup analyses concerning sociodemographic variables. The results suggest that psychiatric patients suffer from multiple metabolic disturbances in comparison to the general population. Monitoring weight, waist circumference, blood pressure and cholesterol regularly is, therefore, highly relevant.

Does olanzapine help with schizophrenia?

Background: Antipsychotic drugs (APDs), olanzapine and clozapine, do not effectively address the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia and can cause serious metabolic side-effects. Liraglutide is a synthetic glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist with anti-obesity and neuroprotective properties. The aim of this study was to examine whether liraglutide prevents weight gain/hyperglycaemia side-effects and cognitive deficits when co-administered from the commencement of olanzapine and clozapine treatment. Methods: Rats were administered olanzapine (2 mg/kg, three times daily (t.i.d.)), clozapine (12 mg/kg, t.i.d.), liraglutide (0.2 mg/kg, twice daily (b.i.d.)), olanzapine + liraglutide co-treatment, clozapine + liraglutide co-treatment or vehicle (Control) ( n = 12/group, 6 weeks). Recognition and working memory were examined using Novel Object Recognition (NOR) and T-Maze tests. Body weight, food intake, adiposity, locomotor activity and glucose tolerance were examined. Results: Liraglutide co-treatment prevented olanzapine- and clozapine-induced reductions in the NOR test discrimination ratio ( p < 0.001). Olanzapine, but not clozapine, reduced correct entries in the T-Maze test ( p < 0.05 versus Control) while liraglutide prevented this deficit. Liraglutide reduced olanzapine-induced weight gain and adiposity. Olanzapine significantly decreased voluntary locomotor activity and liraglutide co-treatment partially reversed this effect. Liraglutide improved clozapine-induced glucose intolerance. Conclusion: Liraglutide co-treatment improved aspects of cognition, prevented obesity side-effects of olanzapine, and the hyperglycaemia caused by clozapine, when administered from the start of APD treatment. The results demonstrate a potential treatment for individuals at a high risk of experiencing adverse effects of APDs.

Is Clozapine an antipsychotic?

Clozapine has proved to be an effective antipsychotic for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia – characterised by the persistence of symptoms despite optimal treatment trials with at least two different antipsychotics at adequate dose and duration – but its use is hampered by adverse effects. The development of clozapine-induced diabetes is commonly considered to arise as part of a metabolic syndrome, associated with weight gain, and thus evolves slowly. We present the case of an individual with refractory schizophrenia and metformin-controlled diabetes who developed rapid-onset insulin-dependent hyperglycaemia immediately after starting clozapine. Given the refractory nature of his illness, the decision was made to continue clozapine and manage the diabetes. This case supports the existence of a more direct mechanism by which clozapine alters glycaemic control, aside from the more routine slow development of a metabolic syndrome. Declaration of interest S.S.S. is supported by a European Research Council Consolidator Award (Grant Number 311686) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. Copyright and usage © The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2017. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Non-Commercial, No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND) license.

What are the factors that should be considered when monitoring patients on atypical antipsychotics?

Based on the results of this study, younger patients should be considered to be at high risk for developing diabetes. Therefore, it is extremely important to monitor these patients more closely for any changes in endocrine function. Also, atypical antipsychotics such as ziprasidone and aripiprazole, which do not seem to pose a high risk of diabetes, should be strongly considered when initiating drug therapy . 12

How to prevent diabetes with atypical antipsychotics?

Diabetes prevention should begin with the careful selection of an atypical antipsychotic; it is recommended to use the lower-risk agents ziprasidone or aripiprazole. Patients should also be encouraged to exercise at least 30 minutes a day 7 days a week and follow a diet like the American Heart Association “Step 2” diet (Table 13 ). There are also pharmacologic options for preventing type 2 diabetes; recent studies have shown that metformin can be added to a patient’s drug regimen to not only prevent metabolic changes, but also to treat atypical antipsychotic—induced type 2 diabetes. 14

Which antipsychotics cause the most metabolic dysfunction?

Most likely, it is a combination of these effects. Of the atypical antipsychotics, clozapine and olanzapine are associated with the highest incidence of metabolic dysfunction, whereas ziprasidone and aripiprazole are considered to be the least risky.

Why are schizophrenics at risk for diabetes?

There is not a clear understanding why schizophrenic patients are at an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Schizophrenic patients have a number of risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including family history, increased body mass index (BMI), sedentary lifestyle associated with the disorder, and the use of atypical antipsychotic ...

What are the causes of weight gain with antipsychotics?

Possible explanations for the weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics include the antagonism of hypothalamic histaminergic H1 receptors, serotonergic 5-HT2C receptors, and/or adrenergic alpha 2 receptors. The antagonism of H1 receptors is thought by some to be the best predictor of antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

When did the FDA start monitoring antipsychotics?

In response to the FDA warning concerning atypical antipsychotics and the risk of type 2 diabetes, the American Diabetes Association and the American Psychiatry Association introduced monitoring guidelines for patients taking antipsychotic medication in 2004.

Do atypical antipsychotics increase risk of diabetes?

Patients with schizophrenia and other disorders who take atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for an increased risk for diabetes.