Well, if used appropriately, opioids can significantly improve pain with relatively tolerable side effects. A short-term course of opioids (typically three to seven days) prescribed following an injury, like a broken bone, or after a surgical procedure, is usually quite safe.

Full Answer

How long should opioids be prescribed for pain?

· Neuropathic: This is a type of pain that is caused by a direct injury to the nerve itself. This type of pain is commonly seen in people with diabetes, neurologic issues, or prior amputations. Opioids are not effective in treating this type of pain. Time course: Acute: Pain lasting less than three to six months (often much less). It typically goes away when the …

Are opioids becoming more popular for chronic pain treatment?

Opiates can be formulated to treat most any type of pain symptom; Opiates can be formulated to produce both short-term and long-term, pain-relieving effects; While the benefits of opiate-based pain management therapy are many, using these drugs for longer than three months at a time opens a person up to the dangers of abuse and addiction. How Opiates Work Mechanism of …

What should clinicians consider before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain?

Opioids have been regarded for millennia as among the most effective drugs for the treatment of pain. Their use in the management of acute severe pain and chronic pain related to advanced medical illness is considered the standard of care in most of the world.

What are some pain management options for opiate addicts?

For chronic pain, such as headache and abdominal pain, often we want pain resolution so badly that we prescribe an opioid, which in many cases has not been proved very helpful for decreasing pain and can result in worsening of functioning and additional side effects. Is there a difference between physical dependence and addiction? Yes.

When should I take opioids for pain?

Prescription opioids are used mostly to treat moderate to severe pain, though some opioids can be used to treat coughing and diarrhea. People misuse prescription opioids by taking the medicine in a way other than prescribed, taking someone else's prescription, or taking the medicine to get high.

Are opioids the best solution for pain management?

Opioids are powerful drugs, but they are usually not the best way to treat long-term (chronic) pain, such as arthritis, low back pain, or frequent headaches. If you take opioids for a long time to manage your chronic pain, you may be at risk of addiction.

How effective are opioids at treating pain?

Findings In this meta-analysis that included 96 randomized clinical trials and 26 169 patients with chronic noncancer pain, the use of opioids compared with placebo was associated with significantly less pain (−0.69 cm on a 10-cm scale) and significantly improved physical functioning (2.04 of 100 points), but the ...

When is chronic pain too much?

Memory and concentration: Chronic pain can affect one's ability to remember information—ultimately interfering with long-term memory and concentration. A study at the University of Alberta indicated that two-thirds of tested participants with chronic pain showed impaired memory and concentration.

What do you do when pain meds don't work?

If your pain medication isn't working, call your health care provider. Remember: Don't change the dosage without talking to your health care provider. Don't abruptly stop taking your medication.

What are the pros of opioids?

If taken as indicated, you can reap the benefits of opioids, which is greater pain relief when you need it most. Those suffering from debilitating pain experience tremendous relief using opioids, which is why they are appropriate drugs for specific situations and people.

Are opioids effective for long-term use?

Key Messages. Opioids are associated with small improvements versus placebo in pain and function, and increased risk of harms at short-term (1 to <6 months) followup; evidence on long-term effectiveness is very limited, and there is evidence of increased risk of serious harms that appear to be dose dependent.

What is a good substitute for opioids?

There are many non-opioid pain medications that are available over the counter or by prescription, such as ibuprofen (Motrin), acetaminophen (Tylenol), aspirin (Bayer), and steroids, and some patients find that these are all they need.

What can be used instead of opioids?

Non-opioid medications may be beneficial in helping to control chronic pain. Some examples of non-opioid pain medications include over the counter medications such as Tylenol (acetaminophen), Motrin (ibuprofen), and Aleve (naproxen). Some prescription medications may also be used to manage pain.

What is the strongest non-opioid pain medication?

Many patients find that ibuprofen, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID), is all they need. In cases where ibuprofen alone is not enough, studies show that a combination of ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and acetaminophen (Tylenol) actually works better than opioids following dental surgery.

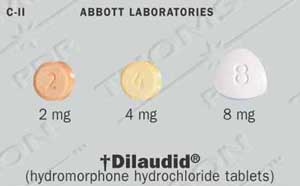

What are the 3 most commonly used opioids?

Common types are oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), morphine, and methadone. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid pain reliever. It is many times more powerful than other opioids and is approved for treating severe pain, typically advanced cancer pain1.

How Opiates Work

Opiates work by binding to specific cell receptor sites within the brain, central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. These interactions cause the release of endorphin chemicals, which act as the body’s own pain-relief agents.

When to Get Opiate Addiction Treatment Help

Opiates not only interfere with the brain’s chemical system, but also impair the brain’s reward system functions. The reward system determines what a person’s priorities are, what motivates him or her. It also dictates thinking patterns, emotional responses and for the most part shapes a person’s behaviors throughout any given day.

Why do people take opioid pain relievers?

Opioid pain relievers are commonly prescribed to patients struggling with chronic pain, as well as those undergoing surgery or healing from an injury. Opioids have been around a long time, but the vast cultural acceptance of these pain relievers, alongside the tendency to prescribe them over other alternatives, has led to a crisis. Opioids are extremely addictive, and many patients begin taking them without a realistic understanding of their potential for abuse. For those that become addicted, maintaining access to opioids can take precedence over personal responsibilities and health. Opioid addiction leads to a wide array of physical and mental health issues, and treatment usually requires professional intervention.

Which pain medication has the best results?

In the study mentioned above, the combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen produced the best results, with only 16 patients needing to be treated for 10 of these patients to see at least 50% pain relief. Both acetaminophen and ibuprofen are over-the-counter drugs. Ibuprofen is a medication in the NSAID category that is not addictive or habit-forming, and acetaminophen, also known as Tylenol, is similarly low risk when it comes to the potential for addiction.

How effective is Oxycodone?

A review conducted by The Cochrane Collaboration found that in the case of oxycodone, 46 people would need to be treated with the medication to produce 10 patients with at least 50% pain relief. When oxycodone is combined with acetaminophen, as is the case with the medication Percocet, the results are a bit better, with only 27 people needing to be treated to see 50% pain relief in 10 of those patients. Either way, these numbers don’t represent what we would expect to see with medications most people consider the most powerful and effective option available.

Do opioids help with back pain?

A review of studies conducted regarding different types of pain and the efficacy of various medications has also concluded that opioids are surprisingly ineffective. Dental pain appears to respond better to an ibuprofen and acetaminophen combination, as do several kinds of back pain. Furthermore, in a study looking at patients who received opioids early on for spinal disc herniation, patients were found to have a higher rate of back surgery and an increased risk of opioid dependence in four years. For those suffering from chronic pain, it is important to note that several studies have found no significant benefit to long-term opioid use. While it appears chronic pain sufferers may experience some relief from opioids in the first few months of taking these medications, the pain relief does not last, and many risks tend to follow.

What is the most effective pain medication?

Opioids have been regarded for millennia as among the most effective drugs for the treatment of pain. Their use in the management of acute severe pain and chronic pain related to advanced medical illness is considered the standard of care in most of the world. In contrast, the long-term administration of an opioid for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain continues to be controversial. Concerns related to effectiveness, safety, and abuse liability have evolved over decades, sometimes driving a more restrictive perspective and sometimes leading to a greater willingness to endorse this treatment. The past several decades in the United States have been characterized by attitudes that have shifted repeatedly in response to clinical and epidemiological observations, and events in the legal and regulatory communities. The interface between the legitimate medical use of opioids to provide analgesia and the phenomena associated with abuse and addiction continues to challenge the clinical community, leading to uncertainty about the appropriate role of these drugs in the treatment of pain. This narrative review briefly describes the neurobiology of opioids and then focuses on the complex issues at this interface between analgesia and abuse, including terminology, clinical challenges, and the potential for new agents, such as buprenorphine, to influence practice.

What is tolerance to opioids?

According to the consensus document, tolerance is defined as a decreased subjective and objective effect of the same amount of opioids used over time, which concomitantly requires an increasing amount of the drug to achieve the same effect. Although tolerance to most of the side effects of opioids (e.g., respiratory depression, sedation, nausea) does appear to occur routinely, there is less evidence for clinically significant tolerance to opioids– analgesic effects ( Collett, 1998; Portenoy et al., 2004 ). For example, there are numerous studies that have demonstrated stable opioid dosing for the treatment of chronic pain (e.g., Breitbart, et al., 1998; Portenoy et al., 2007) and methadone maintenance for the treatment of opioid dependence (addiction) for extended periods ( Strain and Stitzer, 2006 ). However, despite the observation that tolerance to the analgesic effects of opioid drugs may be an uncommon primary cause of declining analgesic effects in the clinical setting, there are reports (based on experimental studies) that some patients will experience worsening of their pain in the face of dose escalation ( Ballantyne, 2006 ). It has been speculated that some of these patients are not experiencing more pain because of changes related to nociception (e.g. progression of a tissue-injuring process), but rather, may be manifesting an increase in pain as a result of the opioid-induced neurophysiological changes associated with central sensitization of neurons that have been demonstrated in preclinical models and designated opioid-induced hyperalgesia ( Mao, 2002; Angst & Clark, 2006 ). Analgesic tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia are related phenomena, and just as the clinical impact of tolerance remains uncertain in most situations, the extent to which opioid-induced hyperalgesia is the cause of refractory or progressive pain remains to be more fully investigated. Physical dependence represents a characteristic set of signs and symptoms (opioid withdrawal) that occur with the abrupt cessation of an opioid (or rapid dose reduction and/or administration of an opioid antagonist). Physical dependence symptoms typically abate when an opioid is tapered under medical supervision. Unlike tolerance and physical dependence which appear to be predictable time-limited drug effects, addiction is a chronic disease that “represents an idiosyncratic adverse reaction in biologically and psychosocially vulnerable individuals” ( ASAM, 2001 ).

Can opioids be used for chronic pain?

At intake, a substantial number of patients in both groups were apparently receiving inappropriate opioid therapy for chronic pain (60% were being treated with short-acting opioids and 49% were taking opioids on demand). At the 12 month follow-up, 86% of MPC patients were receiving long-acting opioids and 11% took opioids on demand. There was no change in the administration pattern in the GP group. These findings suggest that a significant proportion of opioid-treated CNMP patients may be receiving inappropriate opioid treatment and that educating general practitioners in pain medicine may require more than initial supervision.

Can opioids help with CNMP?

This consensus, however, has received little support in the literature. Systematic reviews on the use of opioids for diverse CNMP disorders report only modest evidence for the efficacy of this treatment ( Trescot et al., 2006; 2008 ). For example, a review of 15 double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trials reported a mean decrease in pain intensity of approximately 30% and a drop-out rate of 56% only three of eight studies that assessed functional disturbance found improvement ( Kalso, Edwards, Moore, & McQuay, 2004 ). A meta-analysis of 41 randomized trials involving 6,019 patients found reductions in pain severity and improvement in functional outcomes when opioids were compared with placebo ( Furlan, Sandoval, Mailis-Gagnon, & Tunks, 2006 ). Among the 8 studies that compared opioids with non-opioid pain medication, the six studies that included so-called “weak” opioids (e.g., codeine, tramadol) did not demonstrate efficacy, while the two that included the so-called “strong” opioids (morphine, oxycodone) were associated with significant decreases in pain severity. The standardized mean difference (SMD) between opioid and comparison groups, although statistically significant, tended to be stronger when opioids were compared with placebo (SMD = 0.60) than when strong opioids where compared with non-opioid pain medications (SMD = 0.31). Other reviews have also found favorable evidence that opioid treatment for CNMP leads to reductions in pain severity, although evidence for increase in function is absent or less robust ( Chou, Clark, & Helfand, 2003; Eisenberg, McNicol, & Carr, 2005 ). Little or no support for the efficacy of opioid treatment was reported in two systematic reviews of chronic back pain ( Deshpande, Furlan, Mailis-Gagnon, Atlas, & Turk, 2007; Martell, et al., 2007 ). Because patients with a history of substance abuse typically are excluded from these studies, they provide no guidance whatsoever about the effectiveness of opioids in these populations.

Is chronic pain a substance abuse disorder?

A relatively high prevalence of substance abuse disorders among persons with chronic pain can also be inferred by the high co-occurrence of these two disorders. There have been several reports that the prevalence of chronic pain among persons with opioid and other substance use disorders is substantially higher than the pain prevalence found in the general population ( Breitbart, et al., 1996; Brennan, Schutte, & Moos, 2005; Jamison, Kauffman, & Katz, 2000; Rosenblum et al., 2003; Sheu, et al., 2008 ).

How prevalent is substance abuse in chronic pain?

One 1992 literature review found only seven studies that utilized acceptable diagnostic criteria and reported that estimates of substance use disorders among chronic pain patients ranged from 3.2% – 18.9% ( Fishbain, Rosomoff, & Rosomoff, 1992 ). A Swedish study of 414 chronic pain patients reported that 32.8% were diagnosed with a substance use disorder ( Hoffmann, Olofsson, Salen, & Wickstrom, 1995 ). In two US studies, 43 to 45% of chronic pain patients reported aberrant drug-related behavior; the proportion with diagnosable substance use disorder is unknown ( Katz et al., 2003 ; Passik et al., 2004 ). All these studies evaluated patients referred to pain clinics and may overstate the prevalence of substance abuse in the overall population with chronic pain.

Can withdrawal from opioids cause pain?

For example, based on anecdotal evidence from chronic pain patients, withdrawal from opioids can greatly increase pain in the original pain site. These phenomena suggest the need to carefully assess the potential for withdrawal during long-term opioid therapy (e.g, at the end of a dosing interval or during periods of medically-indicated dose reduction).

How to get patients to take less opioids?

Patients do better and end up taking fewer opioids if they follow up with their physicians and understand opioid treatment expectations from the beginning. Encourage nonopioid medications and nonpharmacologic pain treatments, as well as some physical activity every day. Discourage patients from being inappropriately sedentary during the healing process.

What are nonpharmacologic treatments for pain?

We must communicate that nonpharmacologic treatments for pain, such as ice, heat, diaphragmatic breathing or meditation, can be effective and part of a thoughtful pain management plan.

Can you take opioids until pain resolves?

It is not beneficial to expect patients will take opioids until their pain resolves. There are so many factors playing a role in the pain experience that this practice, in part, may be responsible for the opioid crisis we are facing today.

How to help patients recover from surgery?

Remind patients function is key to recovery. We need to encourage patients that despite having pain, they need to function appropriately for the time. For example, if the surgeon expects the patient to be up and out of bed the day after surgery, this should be conveyed presurgically to the patient. The provider's responsibility is then to provide medications to reduce pain so the patient can accomplish this task, such as providing a pain medication dose 30 minutes prior to physical activity. And encouraging patients that mobility is important in their ability to heal after a surgical procedure or trauma is an important aspect of their rehabilitation.

Can opioids be used for acute pain?

We need to be vigilant for side effects, such as respiratory depression, sedation, nausea, constipation and pruritus. At the same time, we need to consider nonopioid medications as adjuncts to treat pain via a different modality.

Can you have physical dependence on opioids?

Yes. Physical dependence on an opioid occurs in humans and in lab animals. It happens when a patient has received opioids for approximately five days or more and develops withdrawal symptoms — such as tachycardia, goose flesh, diarrhea or diaphoresis — when the drug is withdrawn.

Can opioids help with pain?

For chronic pain, such as headache and abdominal pain, often we want pain resolution so badly that we prescribe an opioid, which in many cases has not been proved very helpful for decreasing pain and can result in worsening of functioning and additional side effects.

How do opioids help with pain?

Opiates suppress pain, reduce anxiety, and at sufficiently high doses produce euphoria. Most can be taken by mouth, smoked, or snorted, although addicts often prefer intravenous injection, which gives the strongest, quickest pleasure.

How to treat opioid addiction?

For some people with opioid use disorder (the new terminology instead of addiction), the beginning of treatment is detoxification — controlled and medically supervised withdrawal from the drug. (By itself, this is not a solution, because most people with opioid use disorder resume taking the drug unless they get further help.) The withdrawal symptoms — agitation; anxiety; tremors; muscle aches; hot and cold flashes; sometimes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea — are not life-threatening, but are extremely uncomfortable. The intensity of the reaction depends on the dose and speed of withdrawal. Short-acting opiates, like heroin, tend to produce more intense but briefer symptoms.

What is the beginning of treatment for opioid use disorder?

For some people with opioid use disorder (the new terminology instead of addiction), the beginning of treatment is detoxification — controlled and medically supervised withdrawal from the drug. (By itself, this is not a solution, because most people with opioid use disorder resume taking the drug unless they get further help.)

Why do people turn to heroin?

Because doctors have needed to reduce opioid prescribing, many people have needed to turn to street dealers to get drugs. But prescription narcotics are expensive. So people have often switched to heroin, which is much cheaper. And street heroin today is commonly laced with the even more dangerous drug fentanyl.

Is opiate addiction a physical dependency?

This physical dependence is not equivalent to addiction. Many patients who take an opiate for pain are physically dependent but not addicted: The drug is not harming them, and they do not crave it or go out of their way to obtain it.

Why do opiates cause withdrawal?

In anyone who takes opiates regularly for a long time, nerve receptors are likely to adapt and begin to resist the drug, causing the need for higher doses. The other side of this tolerance is a physical withdrawal reaction that occurs when the drug leaves the body and receptors must readapt to its absence.

Why is heroin the most popular drug?

Heroin has long been the favorite of street addicts because it is several times more potent than morphine and reaches the brain especially fast, producing a euphoric rush when injected intravenously.

What is the opioid prescribed for?

Background. Opioids are commonly prescribed for pain. An estimated 20% of patients presenting to physician offices with noncancer pain symptoms or pain-related diagnoses (including acute and chronic pain) receive an opioid prescription ( 1 ).

What is the CDC guideline for opioids?

This guideline provides recommendations for primary care clinicians who are prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care. The guideline addresses 1) when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain; 2) opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation; and 3) assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use. CDC developed the guideline using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, and recommendations are made on the basis of a systematic review of the scientific evidence while considering benefits and harms, values and preferences, and resource allocation. CDC obtained input from experts, stakeholders, the public, peer reviewers, and a federally chartered advisory committee. It is important that patients receive appropriate pain treatment with careful consideration of the benefits and risks of treatment options. This guideline is intended to improve communication between clinicians and patients about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain, improve the safety and effectiveness of pain treatment, and reduce the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy, including opioid use disorder, overdose, and death. CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain ( http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38025) as well as a website ( http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribingresources.html) with additional tools to guide clinicians in implementing the recommendations.

Can opioids be used for chronic pain?

Although the transition from use of opioid therapy for acute pain to use for chronic pain is hard to predict and identify , the guideline is intended to inform clinicians who are considering prescribing opioid pain medication for painful conditions that can or have become chronic.

Is opioid pain medication overprescribed?

Across specialties, physicians believe that opioid pain medication can be effective in controlling pain, that addiction is a common consequence of prolonged use, and that long-term opioid therapy often is overprescribed for patients with chronic noncancer pain ( 27 ).

What are the concerns of opioids?

Primary care clinicians report having concerns about opioid pain medication misuse, find managing patients with chronic pain stressful, express concern about patient addiction, and report insufficient training in prescribing opioids ( 26 ). Across specialties, physicians believe that opioid pain medication can be effective in controlling pain, that addiction is a common consequence of prolonged use, and that long-term opioid therapy often is overprescribed for patients with chronic noncancer pain ( 27 ). These attitudes and beliefs, combined with increasing trends in opioid-related overdose, underscore the need for better clinician guidance on opioid prescribing. Clinical practice guidelines focused on prescribing can improve clinician knowledge, change prescribing practices ( 28 ), and ultimately benefit patient health.

How many people were prescribed opioids in 2005?

On the basis of data available from health systems, researchers estimate that 9.6–11.5 million adults, or approximately 3%–4% of the adult U.S. population, were prescribed long-term opioid therapy in 2005 ( 15 ). Opioid pain medication use presents serious risks, including overdose and opioid use disorder.

What is chronic pain?

Chronic pain can be the result of an underlying medical disease or condition, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or an unknown cause ( 4 ). Estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain vary, but it is clear that the number of persons experiencing chronic pain in the United States is substantial.

What is the best medication for acute pain?

Prescription opioids (like hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine) are one of the many options for treating severe acute pain. While these medications can reduce pain during short-term use, they come with serious risks including addiction and death from overdose when taken for longer periods of time or at high doses.

What pain relievers are available?

Pain relievers like ibuprofen, naproxen, and acetaminophen

Why do people take opioid painkillers?

When people experience acute pain, such as the pain one might experience after surgery, or from an injury such as a broken bone, they may be given opioid painkillers to help manage their pain for a short period. 2 While many people take a short-term course of opioids for acute pain without any problem, the inherently rewarding properties of these drugs sometimes prompt their misuse, which could eventually give rise to opioid use disorders and increase certain health risks such as overdose. 2

What are some alternatives to opioids?

Alternatives to Opioids for Chronic Pain. Non-Opioid Pain Medications. Managing Pain Without Drugs. Opioid Addiction Treatment. Managing Chronic Pain in Recovery. Pain is part of the usual human experience, but at times, pain can be intense and overwhelming. Physicians may prescribe a short-term course of opioid painkillers after surgery ...

What are some ways to help with pain?

Yoga, which is based on Hindi practices and uses a holistic approach to mind, body, and spirit and can help manage pain. Mindfulness meditation. Exercise, including therapeutic exercises.

What are some alternatives to acetaminophen?

Beta-blockers, including esmolol and labetalol. Anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin and pregabalin. Antidepressants, such as duloxetine, amitriptyline, and nortriptyline. While some of these alternative options are more effective than others for different types of pain, and while they may have certain risks ...

Can opioids be used to control pain?

Many people assume that opioids are the only viable option to control pain, whether acute or chronic. However, non-opioid drugs, alternative therapies (e.g., yoga, acupuncture, physical therapy), and counseling can also be used to manage pain. 8, 9 Some people may opt for alternatives to medication because they might have a history of an opioid use disorder or fear they may develop one.

Can non-opiod pain medications be used for chronic pain?

While some of these alternative options are more effective than others for different types of pain, and while they may have certain risks of their own, studies indicate that non-opioid medications can be effective for managing various chronic pain syndromes. 4

How long does pain last?

Chronic pain is pain that lasts longer than 3 months, or that which persists beyond the time of a normal healing process. 3 It has been estimated that 100 million Americans suffer pain daily, but many studies don’t support the long-term benefits of opioid use in managing these chronic pain scenarios. 4.

Surveillance Reports

Surveillance Report 1 (dated November 2021) and Surveillance report 2 (dated February 2022) include literature searches updated since the systematic review was posted in April 2020, putting newly identified studies in the context of what is known. The next surveillance report will be available in May 2022.

Purpose of Review

To assess the effectiveness and harms of opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain, alternative opioid dosing strategies, and risk mitigation strategies.

Key Messages

Opioids are associated with small improvements versus placebo in pain and function, and increased risk of harms at short-term (1 to <6 months) followup; evidence on long-term effectiveness is very limited, and there is evidence of increased risk of serious harms that appear to be dose dependent.

Structured Abstract

Objectives. Chronic pain is common, and opioid therapy is frequently prescribed for this condition. This report updates and expands on a prior Comparative Effectiveness Review on long-term (≥1 year) effectiveness and harms of opioid therapy for chronic pain, including evidence on shorter term (1 to 12 months) outcomes.

Suggested Citation

Chou R, Hartung D, Turner J, Blazina I, Chan B, Levander X, McDonagh M, Selph S, Fu R, Pappas M. Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 229. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2015-00009-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 20-EHC011.