It is generally recognized that the first step in treating a patient with acute pulmonary edema is an adequate dose of morphine. This not only relieves anxiety but also ameliorates his dyspnea and fear of impending death.

Full Answer

Should morphine be used to treat acute pulmonary oedema?

Morphine in the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema--Why? Abstract Morphine has for a long time, been used in patients with acute pulmonary oedema due to its anticipated anxiolytic and vasodilatory properties, however a discussion about the …

What are the goals of therapy for acute pulmonary oedema?

[Morphine in the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema] Based on the available studies, the possibility cannot be excluded that the use of morphine results in increased mortality among patients with acute pulmonary oedema. In addition, there is little evidence that the vasodilatory properties of morphine are of any significance for this condition.

What is acute pulmonary oedema?

Oct 18, 2015 · Abstract Morphine has for a long time, been used in patients with acute pulmonary oedema due to its anticipated anxiolytic and vasodilatory properties, however a discussion about the benefits and risks has been raised recently.

What is the prognosis of morphine toxicity in heart failure?

Abstract Morphine has for a long time, been used in patients with acute pulmonary oedema due to its anticipated anxiolytic and vasodilatory properties, however a discussion about the benefits and risks has been raised recently.

How much morphine should I take for pulmonary oedema?

Fig. 1. Algorithm for treatment of acute pulmonary oedema, according to the guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology from 2012, which recommend that 4–8 mg of morphine i.v. may be considered and possibly repeated if needed because of severe anxiety or distress [27].

What is pulmonary oedema?

Acute pulmonary oedema is a common condition in the emergency room, associated with considerable mortality [1], [2]. The oedema develops when the left ventricle fails, making the hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary circulation increase, and therefore fluid builds up in the pulmonary insterstitium and alveoli.

How much morphine is used for vascular resistance?

A trial from 1979 including 28 patients who underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, showed that large doses of morphine (0.5 mg/kg) produced a transient large reduction in peripheral vascular resistance [34]. However, these doses are considerably larger than those we administer today.

What is the drug that inhibits the reabsorption of sodium in Henle's loop and distal

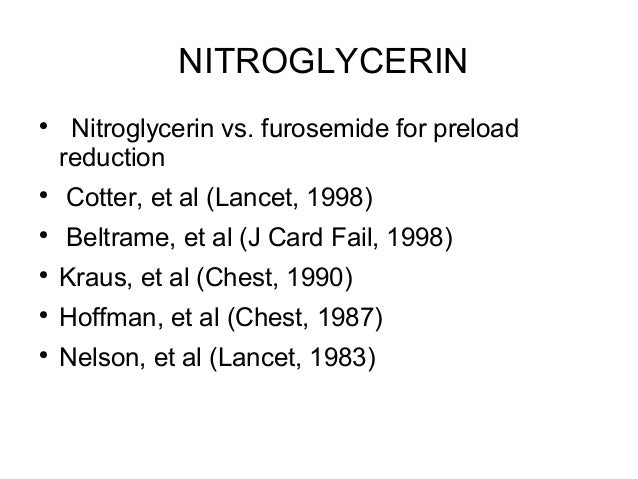

Since the 1960s, three drugs have been most frequently used to achieve these effects, alongside oxygen treatment. It is furosemide, which inhibits reabsorption of sodium in Henle's loop and distal tubuli and thereby increasing excretion of fluids through the kidney.

Does morphine relax the smooth muscles?

In 1994, a trial with vessels from dogs in vitro showed that morphine had a relaxing effect on the smooth muscles in both veins and arteries [18]. The effect was probably caused by histamine release [19], [32]. In 2008, an in-vivo trial in cats, found a morphine-induced dose-dependent vasodilation in the pulmonary vascular bed, expressed by reduced arterial vascular resistance [33]. Whether the physiological effects of morphine are similar in humans and to what extent these effects are significant in the altered haemodynamics of pulmonary oedema, is still scarcely elucidated.

Is morphine a vasodilator?

The third drug, morphine, has been used due to its anticipated anxiolytic and vasodilatory properties. During the last decade, a discussion about the benefits and especially the risks accompanying the use of morphine in cases of pulmonary oedema has been raised [1], [4], [8], [9], [10], [11]. In a retrospective study from 2008 based on the ADHERE registry, morphine given in acute decompensated heart failure was an independent predictor of increased hospital mortality, with an odds ratio of 4.8 (95% CI: 4.52–5.18, p < 0.001) [2].

Can benzodiazepines be used in place of morphine?

Benzodiazepines have been suggested as an alternative for morphine in treatment of pulmonary oedema [4], [26]. However, these types of drugs have not been tested in this clinical situation properly. Nevertheless, this is interesting because benzodiazepines have shown to be efficient anxiolytics over a longer period of time, in addition to the fact that they have positive cardiovascular effects [42]. In a literature study, benzodiazepines were recommended in the treatment of chest pain due to these properties, and several aspects are presented suggesting that they could be an alternative in treatment of pulmonary oedema [42].

Does morphine affect ventilatory response?

Several studies have shown that morphine causes decreased respiratory rate and tidal volume and blunts hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses [ 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 ]. This is thought to be mediated by its agonistic action on μ-receptors located in the central nervous system [ 29, 30 ]. Recently, Zhuang et al. verified a heavy expression of μ-receptors in the caudomedial nucleus tractus solitarius in rats [ 31 ]. This nucleus has chemosensitive neurons activated by hypercapnia and receives input from bronchopulmonary nerve fibres and carotid chemoreceptors involved in respiratory regulation. The study showed that microinjection of a μ-agonist into the nucleus significantly decreased baseline minute ventilation by 18% ( P < 0.01). Hypoxic ventilatory response was profoundly attenuated by 70% due to reduction in both respiratory frequency (47%) and minute ventilation (77%). Hypercapnic ventilator response was attenuated by 21%.

Is morphine vasodilatory?

Both animal and human studies demonstrate that morphine has vasodilatory properties. The effect on pulmonary hemodynamics seems to be neutral and possibly adverse on ventilation. Morphine, along with furosemide and nitrates, is routinely used to treat cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Clinical data on the safety and efficacy of morphine for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema are scarce; however, morphine use has been correlated with increased rates of ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. European and American heart failure guidelines do not recommend routine use of morphine for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema.

Does morphine affect cardiac function?

Studies on morphine’s effect on cardiac function have also shown discrepant results. Lappas et al. studied eight patients with myocardial ischemia requiring revascularization and who had normal baseline systolic function [ 19 ]. Right and left cardiac filling pressures increased with a morphine dose of 1.5 mg/kg or more. However, stroke volume, cardiac output, and systemic arterial pressure decreased after a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. Systemic vascular resistance was unchanged indicating that blood pressure decrement was secondary to decreased cardiac output rather than vasodilation. Correspondingly, other research has shown that inhibition of CNS opioid receptors may increase blood pressure and cardiac output [ 20 ]. More clinically relevant data were presented by Lee and colleagues who administered morphine 15 mg to ten patients with acute transmural myocardial infarction, four were Killip class I, three were Killip class II, and three were Killip class III [ 21 ••]. Invasive and echocardiographic hemodynamic assessment showed no change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, ejection fraction, left ventricular dimensions, or right and left filling pressures. There was, however, a slight increase in pulmonary vascular resistance at 45 min post injection from 132.4 ± 13.8 to 183.1 ± 3.2. Morphine was studied in a cohort of ten patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by systolic dysfunction; each received a dose of 0.2 mg/kg morphine. Subjects had mild negative effect on HR, BP, and SV, and no effect on LV filling pressure [ 22 ]. Due to inconsistent evidence, the act of morphine to relieve cardiac dyspnoea cannot be adequately explained by pulmonary vascular preload reduction. Anxiolysis may be an important contributor, however, literature to support this hypothesis is scant [ 6, 23 ].

Does morphine affect vasoconstrictors?

Zelis et al. studied the morphine response in the upper extremity vasculature of 69 human subjects [ 15 ]. Morphine was observed to induce rapid vasoconstriction lasting 1–2 min followed by a 35% reduction in the venous pressure and a 25% reduction in vascular resistance at 10 min. Arterial blood pressure remained constant, resulting in a 26% increase in blood flow. The physiologic vasoconstrictor response to deep breathing, mental arithmetic, cold, post-Valsalva overshoot, and 45° head-up position was intact. The team attempted to describe the mechanism of morphine’s action by infusing 200 μg/min in the brachial artery and adding promethazine (an antihistamine), propranolol (a beta-adrenergic blocker), and atropine (a cholinergic blocker). No effect was observed on morphine vasodilatory action; however, phentolamine (an alpha-adrenergic agonist) abolished the effect. This suggests that morphine causes vasodilation by reducing central sympathetic efferent discharge. Vismara et al. used a similar technique to compare the vascular response to morphine in 13 subjects with pulmonary oedema and normal subjects. Morphine sulfate was infused at 0.1 mg/kg and a similar venodilatory response was observed; however, there was no significant difference between those with pulmonary oedema and controls [ 16 ]. Morphine was also shown to decrease splanchnic vascular resistance resulting in a 19% increase in splanchnic blood flow without a change in systemic or right atrial pressure when infused at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg to a maximum of 15 mg in 13 patients [ 17 ]. A later investigation by Grossmann et al. demonstrated that infusing morphine with naloxone did not alter its vasodilatory effect on hand veins of healthy volunteers [ 18 ]. Nonetheless, co-infusion with a combination of diphenhydramine (an H1 receptor blocker) and famotidine (an H2 receptor blocker) blunted the vascular response, indicating a histamine-mediated effect, contrary to the results of Zelis et al. Fentanyl did not have a significant effect on peripheral vasculature.

Is morphine good for dyspnoea?

Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (CPE) is the second most common cause of dyspnoea presenting to the emergency department [ 1, 2 ]. Therapy usually targets correction of gas exchange via invasive or non-invasive ventilation, diuresis, and altering pulmonary vascular hemodynamics to decrease capillary leakage [ 3, 4 ]. Morphine has been described to be beneficial in these cases since the 1950s; however, concerns have been raised regarding its efficacy and safety [ 5, 6 ]. We will review the pathophysiology of pulmonary oedema, the rationale of using morphine for CPE, and relevant pharmacodynamic and clinical outcome data.

Is morphine safe for pulmonary oedema?

Morphine is of questionable benefit and may be harmful in treatment of acute pulmonary oedema. Clinical guidelines do not encourage routine use of morphine for pulmonary oedema; other medications for anxiolysis and vasodilation may be preferable.

Is morphine used in CPE?

Morphine use in CPE has been encouraged based on clinical observations of relief of respiratory distress in the absence of data that demonstrates efficacy [ 5, 35, 36 ]. The mnemonic “MONA” encouraged morphine, oxygen, nitrates, and aspirin for treatment of acute myocardial infarction, although the origins of this memory device are unknown [ 37 ]. Table 1 summarizes the available clinical evidence of using morphine for CPE. One major hurdle to studying the efficacy of prehospital CPE-specific therapies is a 23–40% rate of prehospital misdiagnosis of acute obstructive lung disease, infection, or other types of pulmonary oedema as CPE [ 39, 41, 45 ]. A prospective study of 57 patients presenting with acute respiratory failure evaluated prehospital administration of different combinations of morphine, furosemide, and nitrates and showed no benefit of morphine and indicated a signal for worsening ventilation [ 41 ]. Another prospective evaluation of 84 patients receiving morphine for suspected CPE by paramedics illustrated the potential for adverse effects. Respiratory depression was observed in one patient who received morphine by paramedics and was ultimately diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by the physician’s assessment upon arrival in the ED [ 39 ]. A study of prehospital morphine safety examined the prehospital treatment regimens of 319 patients with ADHF; 6% received prehospital morphine with no independent association to change in vital signs or clinical outcomes [ 45 ].

What is the best treatment for pulmonary oedema?

Appropriate prompt therapy can provide rapid improvements in symptoms by reducing pre-load and after-load, or increasing myocardial contractility. Oxygen, loop diuretics, and nitrates are well-established therapeutic options.

Why is diamorphine given?

Most textbooks of acute medicine 1,2 also recommend that intravenous morphine (or diamorphine in the UK) is given to “cause systemic vasodilatation and sedate the patient”, 2 despite the absence of evidence supporting its efficacy.

Does morphine cause respiratory depression?

Treatment with morphine may be associated with respiratory depression in an already hypoxic patient, potentially exacerbating cardiac insufficiency. Respiratory failure secondary to opiates in pulmonary oedema has previously been reported elsewhere. 3.

Can nitrates be used for pulmonary oedema?

We suggest that it is only used in acute pulmonary oedema, with caution, when analgesia is required in association with acute myocardial infarction. The use of titrated intravenous diuretics and nitrates to promote vasodilatation is preferable.

What are the medications used for pulmonary oedema?

Any underlying cause should be identified when starting treatment. The drugs used in treatment include nitrates, diuretics, morphine and inotropes. Some patients will require ventilatory support. A working algorithm for the management of acute pulmonary oedema in the pre-hospital setting is outlined in the Figure.

What is the goal of pulmonary oedema therapy?

The goals of therapy are to improve oxygenation, maintain an adequate blood pressure for perfusion of vital organs, and reduce excess extracellular fluid. The underlying cause must be addressed. There is a lack of high-quality evidence to guide the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema.

What is the goal of a cardiogenic pulmonary oedema echocardiogram?

Once the patient with cardiogenic acute pulmonary oedema has been stabilised the goal of therapy is to improve long-term outcomes. If an echocardiogram shows a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, the focus is to treat any associated conditions. This includes the management of hypertension with antihypertensive drugs, reduction of pulmonary congestion and peripheral oedema with diuretics, and rate control for atrial fibrillation. If there is evidence of a reduced ejection fraction and chronic heart failure then an ACE inhibitor, beta blocker and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist should be considered.2

What is the mortality rate for acute pulmonary oedema?

The one-year mortality rate for patients admitted to hospital with acute pulmonary oedema is up to 40%.3The most common causes of acute pulmonary oedema include myocardial ischaemia, arrhythmias (e.g. atrial fibrillation), acute valvular dysfunction and fluid overload. Other causes include pulmonary embolus, anaemia and renal artery stenosis.1,4Non-adherence to treatment and adverse drug effects can also precipitate pulmonary oedema.

How to improve ventilation for pulmonary oedema?

The first step in improving ventilation for patients with acute pulmonary oedema is to ensure that they are positioned sitting up.1This reduces the ventilation– perfusion mismatch and assists with their work of breathing.

How much oxygen should be given to a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

These include up to 4 L/minute via nasal cannulae, 5–10 L/minute via mask, 15 L/minute via a non-rebreather reservoir mask or high-flow nasal cannulae with fraction of inspired oxygen greater than 35%. For patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the target oxygen saturation is 88–92% and the use of a Venturi mask with inspired oxygen set at 28% is recommended.11

Can furosemide be used for pulmonary oedema?

There is a lack of controlled studies showing that diuretics are of benefit in acute pulmonary oedema. However, diuretics are indicated for patients with evidence of fluid overload.13Loop diuretics such as furosemide reduce preload and should be withheld or used judiciously in patients who may have intravascular volume depletion.9,13